One shortcoming of the public transit compared with private cars is that origin points (and destinations) and the transit stations (or stops) are separated at a distance, and passengers of the public transit have to go to stations (or stops) by foot, by bicycle, and so on. Accessibility, which can be measured by the length between origin points and stops (or stations) or by the length between stops (or stations) and termination points, has a significant influence on service quality of the public transit [1-2] and ridership of the public transit [3-6]. Since there is a significant effect of accessibility on service quality and ridership of public transit, in order to improve accessibility of the public transit, lots of efforts have been made by transit agencies to improve accessibility of the public transit, such as improvement of environment in which the last-mile trip takes place, construction of bicycle lanes, implementation of bicycle-sharing systems.

As an environmentally friendly, healthy, and flexible transportation mode, the bicycle is suitable for a feeder service of the public transit. For example, Murphy[7] finds 39% of respondents use shared-bicycle as a feeder mode in their trip. In lots of cities in developing countries, the public transit, such as the bus transit, the metro as well as the BRT, plays a leading role in urban travelers' daily commute. Bicycles are used mainly as a feeder mode of the public transit for access trips and egress trips, i.e., the bicycle is used by a commuter to travel from the original point to the station or from the station to the destination. As a feeder mode, riding the bicycle is usually faster and more comfortable than walking. Thus, the combination of bicycles and public transit could be competitive compared with private car [8-9]. However, private bicycles also suffer from lots of problems. Taking cities in China as an example, private bicycles suffer from bicycle theft and shortage of bicycle stations. Moreover, different from the public transit in America or Europe, buses and metro in cities of China are notoriously crowded, and it is difficult for travelers to take a bicycle onto buses or carriages of the metro. In fact, according to regulations of most public transit agencies in China, only folding bicycles are allowed to be carried on buses and carriages of the metro. Therefore, the usage of private bicycles has declined in recent years in China along with rapid motorization and urbanization. These problems prevent lots of travelers from traveling by transit.

In order to improve the accessibility of the public transit and the service quality of the public transit, it is necessary to alleviate the "last-mile" problem. Lots of cities have paid great attention to the development of the bicycle-sharing system (BSS). As Ji [10] states, "a marriage between public bicycle and rail transit presents new opportunities for sustainable transportation". Over the last few years, BSS has rapidly expanded all over the world. With the development of BSS, shared-bicycles play an important role in the accessibility of the public transit. There are several generations of BSS: "white bikes", "coin deposit system", "IT-based systems", and "multi-modal system" [11-12]. Due to inconvenience and other reasons, the first three generations of BSS (we refer the three generations of BSS as the traditional BSS in this paper) did not develop very well in lots of cities. However, the fourth generation of BSS, the dockless BSS, has become popular. The dockless BSS plays an important role in solving the "last mile" problem of the public transit.

The traditional BSS is a bicycle system with bicycle rental stations. The user borrows a bicycle from a rental station and is required to return the bicycle to another rental station. Usually, the borrowed station and the returned station are not required to be the same. It facilitates one-way users because these users do not have to return the bicycle to the rental station they borrowed from. However, since the bicycle can only be borrowed from a rental station and has to be returned to a rental station, the BSS is less convenient than the private bicycle to some extent.

A survey of the traditional BSS in the University Town of Guangzhou in October 2013 shows that, of the 155 interviewees, only 41 used the traditional BSS (the ratio was not high since the public transit was inconvenient and car-ownership of college students was negligible, and travelers in University Town relied heavily on non-motorized traffic). The reasons that prevented the remaining 114 from using traditional BSS are shown in Table 1.

| Table 1 Reasons that travelers did not use the traditional BSS (multiple choice) |

Problems encountered by the 41 interviewees are shown in Table 2.

| Table 2 Problems that travelers had encountered (multiple choice) |

Although the number of interviewees is not large, it can be figured from the interview that lots of travelers were unsatisfied with the traditional BSS, and there were lots of problems of the traditional BSS. Because of these reasons, the traditional BSS did not develop well in lots of cities.

The smartphone-app-driven dockless BSS has been undergoing great development since the third quarter of 2016. The dockless BSS is a bicycle-sharing system without fixed bicycle stations. One of the dockless BSS, screenshot of the app of Mobike is shown in Fig. 1. There is a built-in GPS system in the bicycle, and the user locates and finds the bicycle through a smartphone app. By scanning the QR code on the bicycle' rear, one can unlock the bicycle. After use, one can leave the bicycle to any legal parking location. The user is charged automatically through the smartphone app. One can download the smartphone app of the dockless BSS and register as a member through it. Therefore, it is much more convenient to become a member using the dockless BSS than the traditional BSS. Since one can find the dockless bicycle through the smartphone app and leave it to any legal location, there are no such problems as "it is troublesome to become a membership", "there are few stations", "there is no parking space at the rental station", "I have no idea where the station is", and so on.

|

Fig.1 A screenshot of the app of Mobike-One of the dockless BSS |

Because the dockless BSS is different from the traditional BSS, components of the service quality of the dockless BSS are different from that of the traditional BSS. Although there are some papers about the service quality of bicycles, most of these papers are about the service quality of the private bicycles or the traditional BSS (we will discuss it in detail in Section 2 of this paper). However, there are few articles involved in the service quality of the dockless BSS. Therefore, there are two primary aims of this study: 1) how to evaluate the service quality of the dockless BSS, which aspect of service quality should be improved firstly; and 2) how users' demographic characters affect their evaluation of the service quality of dockless BSS.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 reviews the existing studies related to the service quality of the bicycle system; Section 3 describes the primary methodology and data collection procedure; Section 4 analyzes the results, and Section 5 concludes this paper.

2 Literature ReviewA summary and comparison of literature involving service quality of bicycle is shown in the Table of Appendix.

Because of service's intangibility as well as its simultaneous production and consumption, there is a great difference between the mechanistic quality and the service quality[13]. Since cyclists usually do not have much information about technical aspects of service quality of the bicycle system, although there is a continuous debate about whether the service quality of the bicycle system should be evaluated from the viewpoint of cyclists or evaluated with objective indicators, most of the literature on service quality of the bicycle system analyze the service quality from the viewpoint of cyclists.

2.1 Components of Service QualityAs to components of service quality of the bicycle system, components vary in different papers.

In Ref.[14], there are 17 factors related to service quality of BSS (more detail about these factors is referred to the Table in Appendix). Ref.[15] only takes into account two categories of service quality: road geometry and surrounding conditions. There are 5 categories of factors in Ref.[16] related to service quality of the bicycle system: the system service, the convenience of renting a bicycle, bicycle condition, supplementary service, and the location of stations. Ref.[17] also takes into account 5 categories of factors: usability, reliability, connectivity, economic efficiency, and mobility. Components of service quality of the BSS in the study of Ref. [18] include: availability, layout of stations, service time, complaint channel, handy service for the public, bicycle's condition, bicycle's appearance, and traveling comfort. Ref. [19] analyzes the importance of bicycle's factors with factor analysis, and it turns out there are 5 latent variables that are important: maintenance, environment, network, design, and personal satisfaction. There are 30 factors involved in the service quality of BSS by Ref. [20]. In the analysis of perceptions of cycling among high school students and their parents, Ref. [21] finds that evaluation of safety and social norms has a great influence on bicycle's mode split of high school students. In Ref. [22], there are several factors affecting the service quality of the BSS, which are convenience of renting a bicycle, convenience of returning the bicycle, numbers, distribution of rental stations, transfer, price, free time, compensation fees, deposit, comfortableness when cycling, bicycle lane, bicycle condition, separation facilities, service time, bicycle dispatch, and staff service. Components of BSS' service quality by Ref. [23] is similar with the Ref. [22]. In the study of Ref. [24], components of BSS' service quality include: subscription fee, comfort, customer care service, distribution of rental stations, bicycle condition. Component of service quality of the Ref. [25] include: bicycle routes, public transit integration, access to public centers, bicycle-friendly workplace, eco-friendliness, flexibility, climate, danger of accidents, climate, safe bicycle parking on the street, speed limit, price, cycling fits into my lifestyle, and topography.

Although there are some articles discussing the reason that prevents people from using shared-bicycle. Ref. [26] finds that there are 6 barriers: cycling infrastructure, safety, distance, physical skill, city topography, climate, and cycling infrastructure. The main reasons preventing people from traveling by shared-bicycle in Ref. [27] are: no need, far away from the rental station, inconvenience, troublesomeness of applying for a card. On the other hand, Ref. [28] finds that factors motivate travelers becoming members of BSS are: preference of cycling's experience, speed, convenience, environment-friendliness, and closeness to origin/destination. Reasons that users travel by shared-bicycle found by Ref.[27] include: better for the environment, flexibility, substitution of public transit, fitness, and so on.

From the above-mentioned articles, although components of the BSS's service quality vary, there are several components that most of these articles have taken into account: safety, convenience, bicycle lane, weather, and locations of bicycle stations.

2.2 Effects of Demographic CharacteristicsSeveral papers[7, 14, 19-20, 24-25, 27, 29-33] involving bicycle service have analyzed the effect of demographic characteristics. More details about demographic characteristic that these papers have analyzed are shown in the Table of Appendix, and effects of these demographic characteristics vary in different articles.

For example, as to the effect of age, Refs. [27, 29] find that travelers' likelihood of using shared-bicycle increases as age increases. On the contrary, Refs. [7, 10] finds that there are more young shared-bicycle users than old shared-bicycle users. Ref. [14] does not find a significant difference of evaluation of service quality between the "≤30" subgroup and the ">30" subgroup. However, Ref. [20] finds that the evaluation of the "0-25" subgroup is more negative than that of the "25-35" subgroup.

As to the effect of gender, there exist inconsistent conclusions. Lots of articles on the effect of gender argue that female is less likely to travel by bicycle and is more critical about the service quality of service quality [7, 10, 14, 24, 32-33]. However, Ref.[19] finds that females show a greater level of importance to factors than males, and Ref. [31] finds that female's favorable attitudes toward cycling are stronger, and Ref. [29] finds that female's likelihood of using BSS is higher than male. Besides, Ref. [20] argues there is no significant difference of evaluation between male and female, and Ref. [27] does not find a significant influence of gender on travelers' mode choice for the feeder.

All the articles related to the impact of frequency agree that frequent cyclists are more positive on the evaluation of service quality of bicycle system and are more likely to travel by bicycle[14, 20, 25, 27, 31].

According to Refs. [7, 29], high-income travelers are more likely to travel by bicycle, and according to Refs. [14, 20], low-income travelers evaluate service quality of the BSS more positively. Conversely, Ref. [33] finds that travelers with high-income in China are less likely to travel by bicycle.

2.3 Brief Summary of Literature Related to BSSAlthough there are several papers on the service quality of BSS, all these papers are about the traditional BSS or the private bicycle, yet there is no paper related to service quality of the dockless BSS. As mentioned above, since the dockless BSS is considerably different from traditional BSS, components of service quality of the dockless BSS are different from that of the traditional BSS as well. Therefore, the result of the traditional BSS may not be suitable for the dockless BSS. Besides, there are still some inconsistencies on effects of demographic characteristics, so it is necessary to evaluate service quality of BSS and analyze effects of demographic characteristics.

3 Methodology and Data CollectionAs mentioned above, since there is a significant difference between the mechanistic quality and the service quality, it is more appropriate to evaluate service quality of the dockless BSS from the viewpoint of shared-bicycle users. In this paper, raw data of service quality of dockless BSS was obtained through cyclists' evaluation. Then we analyzed the raw data with the Rasch Model. After the analysis, the cyclist parameter and the item parameter were obtained. Therefore, this section is arranged as follows: in Section 3.1 we introduce Rasch Model briefly. After that, evaluation items for the dockless BSS are presented.

3.1 Rasch ModelIn this paper, we analyzed service quality of dockless BSS from the viewpoint of dockless BSS users, i.e., we designed a questionnaire which contains several items of service quality of the dockless BSS, and then we investigated users and asked them to evaluate their satisfaction about these items. Users' evaluation of service quality is an ordinal rather than an interval scale. As pointed out by Ref. [34], there are four types of measurement scales: nominal, ordinal, interval, and ratio. With ordinal scale, only the order of the value matters, and the difference between adjacent values is meaningless. For example, in a typical Likert scale which contains 5 levels: "strongly agree", "agree", "undecided", "disagree", and "strongly disagree", all we know is that "strongly agree" > "agree" > "undecided" > "disagree" > "strongly disagree". We do not know the difference between "strongly agree" and "agree" and the difference between "agree" and "undecided" is the same or not. Therefore, traditional methods, such as T-test, linear regression, ANOVA, and so on, are not suitable for ordinal data.

Since the evaluation of dockless BSS users is ordinal data, in order to analyze these data with above-mentioned parametric statistical methods, it is necessary to transform the ordinal data to interval data. In this paper, we analyzed users' evaluation with Rasch Model. Named after Georg Rasch, Rasch Model is a psychometric model used to analyze students' scores initially. In the viewpoint of Rasch Model, the student's score is a function of trade-off between the student's ability and the item's difficulty, i.e., on average, the higher the student's ability is, the higher the student's score is; the higher the item's difficulty is, the lower the student's score on this item is. Through the analysis of student's score with Rasch Model, the scale-free person parameter (student's ability) and the sample-free item parameter (item's difficulty) are obtained. Moreover, the student's ability and the item's difficulty are interval data, and they are on the same unit: logits. Therefore, after analysis with Rasch Model, the student's ability and the item's difficulty can be analyzed with parametric statistical methods. Furthermore, we can compare the student's ability and the item's difficulty.

The Rasch Model was designed to deal with dichotomous data initially (1 and 0 indicate right and wrong, respectively). The probability that person i is correct and wrong on item j are expressed in Eq.(1) and Eq.(2), respectively [14, 20].

| $ P\left( {1|{\theta _i}, {b_j}} \right) = \frac{{\exp \left( {{\theta _i} - {b_j}} \right)}}{{1 + \exp \left( {{\theta _i} - {b_j}} \right)}} $ | (1) |

| $ P\left( {0|{\theta _i}, {b_j}} \right) = \frac{1}{{1 + \exp \left( {{\theta _i} - {b_j}} \right)}} $ | (2) |

where θi and bj represent person i's ability and item j's difficulty, respectively.

As to polytomous rating data, such as Likert scale, person i's probability on item j's score m is expressed by Eq.(3) [14, 20]:

| $ \log \left( {\frac{{{P_{ijm}}}}{{{P_{ij(m - 1)}}}}} \right) = {\theta _i} - \left( {{b_j} + {\tau _{ij}}} \right) $ | (3) |

where Pijm is the probability of person i's score m on item j; , τjm is the step difficulty of item j on score m.

From Eqs. (1) and (2), it can be found that when θi equals to bj, there is a 50% chance that person i is right on item j. The chance person i is right on item j increases as the ability of person i increases and decreases as the difficulty of item j increases. Also, as shown in Eq.(3), the difference between person i's ability θi and item j's difficulty bj plays an important role. As the value of ability minus difficulty increases, the score on the item increases.

By convention, we refer the person parameter and the item parameter as ability and difficulty, respectively. The larger one's ability is, the more positive the person's evaluation of the service quality is. The larger an item's difficulty is, the more negative a person's evaluation of this item is.

3.2 Questionnaire DesignThe measurement of service quality of the dockless originally derived from articles related to service quality of bicycle system as shown in the Table of Appendix. As discussed above, there are lots of differences between the dockless BSS and the traditional BSS. Factors that affect service quality of the dockless BSS are different from that of the traditional BSS. Therefore, we adjusted the original article according to characteristics of the dockless BSS. After that, a pilot survey was conducted in the South China University of Technology, and the measurement items were calibrated according to the pilot survey. The finally determined measurement items are shown in Table 3.

| Table 3 Servie items of the dockcless BSS |

Interviewees were asked to evaluate their satisfaction of the items shown in Table 3 according to their experience during traveling by dockless shared-bicycle with a five-Likert scale: very dissatisfied (1), dissatisfied (2), neither (3), satisfied (4), very satisfied (5). In order to evaluate interviewees' demographic characteristics' impact on the evaluation of service quality, lots of demographic characteristics of interviewees were also investigated: gender, age, education, trip purpose, frequency of traveling by dockless shared-bicycle, private car ownership, monthly income, and monthly consumption.

3.3 Sampling and SurveyThe data is investigated in May 2017 in Guangzhou China.

Only travelers who have used dockless shared-bicycle were investigated. The interviewees were chosen randomly. A total of 365 respondents provided valid questionnaires. The sample size is suitable for the analysis of polytomous Rasch Model [36-37]. With regard to students, since they have no income, we investigated their monthly consumption instead. In terms of interviewees who is not a student, we investigated their monthly income.

As shown in Table 4, more than 60% of interviewees are students. As to gender, there are more male interviewees than female interviewees, and it is consistent with most of the literature on the impact of gender on bicycle use. With regard to age subgroups, most of the dockless shared-bicycle users are between 21 and 30. There are few interviewees who are older than 31. Therefore, we can conclude that most of the cyclists are from the younger generation. In terms of educational background, most of the interviewees have a junior college degree or above, which indicates that most of the interviewees are well-educated, and it is consistent with the investigation of BSS in Hangzhou China by Ref.[20] which argues that most of the users of BSS are well-educated. As to weekly use of dockless shared-bicycle, more than 35% of the interviewees reported using the bicycle more than 5 times per week, indicating that dockless BSS should be one feeder travel mode for urban residents. As mentioned above, since student has no income, we investigated their monthly consumption. From the data, most of the students spend about ¥1 000-¥1 500 per week. As to private car ownership, the ownership is low if we take students into account. But if we only take into account interviewees who are not students, car ownership soars to 41.67%, which is rather high. With regard to monthly income, more than half of the interviewees whose monthly income are between ¥5 000 and ¥10 000.

| Table 4 Descriptive statistics of interviewees |

4 Data Analysis

We analyzed the raw data from the investigation with the Rasch Model firstly. After analysis of these data, the fit statistics and estimation of items' "difficulty" measures are shown in Table 5. All the value of in.msq and out.msq is in the range of [0.5, 1.5], and ptme is significantly greater than 0. Therefore, the fitness of the model in this paper is good and acceptable [38].

| Table 5 Estimation of the item's difficulty and fit statistics |

4.1 Ability Analysis

Except for the item's difficulty, the interviewee's ability is also able to be obtained from the analysis of Rasch Model. The measurement of ability is represented in "logit" units, and ability is interval scale. A lower ability implies a lower evaluation of service quality, and vice versa. To examine whether or not significant differences of ability exist among various subgroups, we analyzed interviewee's ability with one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). The results are shown in Table 6.

| Table 6 Impact of interviewee's demographic character on his/her ability |

There is no significant difference in ability between male and female. The result in this paper is consistent with Ref. [20], but is inconsistent with Refs. [14, 24, 31]: Refs. [14] and [24] find that male is more content than female with regard to service quality of BSS, and Ref. [31] finds that female's favorable attitude toward cycling is stronger.

With regard to education, there exists a significant difference. The average ability decreases with the increase in academic qualifications. Ref. [20] finds that with the increase in academic qualifications, BSS users' evaluation of service quality tends to be more positive on average, although the tendency is not significant at 5% level. Therefore, the result in this paper is inconsistent with Ref. [20].

In terms of the effect of the weekly use of dockless shared-bicycle, although interviewees' evaluation on service quality tends to be more positive as weekly use increases on average, the difference among different subgroups is not significant. Thus the result in this paper is inconsistent with previous research.

As mentioned above, since students have no income, we investigated their monthly consumption. From the data in Table 6, monthly consumption has a significant impact on ability. Students with monthly consumption less than ¥1 000 has a greater ability than students with monthly consumption greater than ¥1 000, and the difference between the "¥1 000-¥1 500" subgroup and the ">¥1 500" subgroup is insignificant (p = 0.410 8). Therefore, we can conclude that students whose monthly consumption are less than ¥1 000 are more satisfied than students whose monthly consumption are more than ¥1 000.

Private car ownership has no effect on interviewees' ability. The result is consistent with Ref. [14]. Meanwhile, monthly income has no effect on interviewees' ability, and the result is consistent with Ref. [14], but inconsistent with Ref. [20] which argues that users' satisfaction increases as monthly income increases.

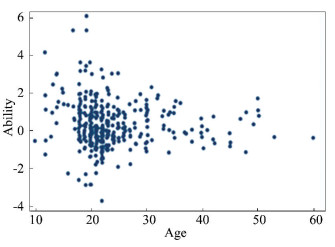

As the impact of age, through regression of ability on age, it is found that age has no significant impact on ability (p = 0.120), the results are shown in Fig. 2. The result in this paper is inconsistent with Ref. [20], but consistent with Ref. [14].

|

Fig.2 Relationship of age and ability |

4.2 Difficulty Analysis

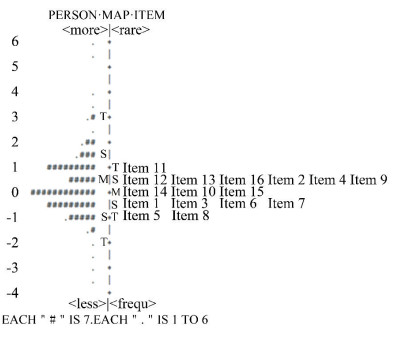

The item's difficulty is shown in Table 5. We rearranged these values and compared them with a picture shown in Fig. 3.

|

Fig.3 Comparison of items' difficulty |

As discussed above, the larger the item's difficulty is, the more dissatisfied the user on this item is. If an item's difficulty is smaller than zero, then it is relatively easy for interviewees to overcome the item and lots of interviewees are dissatisfied with this item. From Fig. 4 and Table 5, the greatest difficulty is Item 11 (Cycling under the adverse weather) - 1.09 logits. Dockless shared-bicycle users are dissatisfied of cycling under the adverse weather the most. Since it often rains in Guangzhou, and the temperature is rather high in summer, the weather condition is not pleasant, thus the relevant department should pay attention to the influence of adverse weather. Except for Item 11, interviewees are rather dissatisfied with Item 13 (Disturbance from pedestrians and cars, 0.75 logits) and Item 12 (Continuity of the bicycle lane, 0.59 logits). These two items are related to service quality of the bicycle lane. It can be concluded that the bicycle lane is not good enough in Guangzhou. Therefore, much more effort should be made to improve the service quality of the bicycle lane. Also, more bicycle lane should be constructed. The fourth and the fifth greatest difficulty are Item 16 (Complaint channel and staff service, 0.52 logits) and Item 2 (Convenience of finding a shared-bicycle, 0.32 logits), respectively.

|

Fig.4 Wright map of service quality of dockless BSS |

On the other hand, Item 8 (Appearance of the shared-bicycle) has the smallest difficulty. Except for Item 8, the other simple items include Item 5 (Price), Item 3 (Convenience of unlocking a bicycle), and Item 7 (Comfort when cycling with the shared-bicycle). Therefore, users are satisfied with the appearance of the shared-bicycle, the price, and the convenience of unlocking a bicycle the most. Besides, although users are dissatisfied with service quality of the bicycle lane, they feel satisfied when cycling.

4.3 Comparison of Ability and DifficultyAs mentioned above, through analysis of raw data with Rasch Model, the interviewee's ability and the item's difficulty were obtained. Since ability and difficulty are interval scales and are on the same axis (logits), we can compare ability and difficulty. Fig. 4 depicts the Wright map presenting the distribution of the item's difficulty and the interviewee's ability, with the distribution of ability and difficulty on the left and right side, respectively. The left-hand side is ranked by the level of ability, and an interviewee with a higher ability is located at a higher level. Similarly, the right-hand side is ranked by the level of difficulty, and an item with higher difficulty is located at a higher level. Notations "M", "S", "T" on the left side represent mean, one standard deviation, and two standard deviations of the ability, respectively. So does the right side. If an interviewee's ability equals to the item's difficulty, then the interviewee has a 50% chance of overcoming the item difficulty. The probability of an interviewee overcoming an item increases as the interviewee's ability increases, and decreases as the item's difficulty increases[14].

From Fig. 4, it can be seen the average of ability is larger than the average of difficulty, therefore, interviewees were satisfied with service quality of the dockless BSS in general. Compared with the distribution of ability, difficulties are rather concentrated. All the difficulties are located within one deviation away from the mean of ability. Relatively, ability distributes rather dispersedly. Also, we can analyze the relationship between items' difficulty and interviewees' ability with the Wright map. Take the most difficult item, Item 11 (Cycling under the adverse weather), as an example. It can be found from the map that the difficulty of Item 11 is larger than the average of interviewees' abilities, therefore, less than half of interviewees overcame the difficulty (71 out of 365).

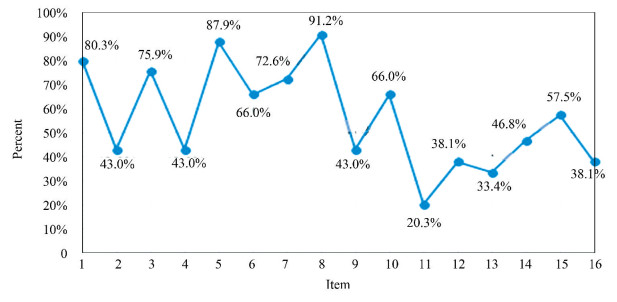

As mentioned above, if an interviewee's ability equals to the item's difficulty, then the interviewee has a 50% chance of overcoming the item difficulty. The probability of an interviewee overcoming an item increases as the interviewee's ability increases, and decreases as the item's difficulty increases. Therefore, in order to analyze the relationship between the interviewee's ability and the item's difficulty more deeply, we compared every interviewee's ability and every item's difficulty. Fig. 5 shows the percentage of the interviewees whose ability is larger than the item's difficulty.

|

Fig.5 Percentage of interviewees whose ability overcome the item's difficulty |

It can be found from Fig. 5 that only 20.3%, 33.4%, 38.1%, and 38.1% of the interviewees overcame Item 11 (Cycling under the adverse weather), Item 13 (Disturbance from pedestrians and cars), Item 12 (Continuity of the bicycle lane), and Item 16 (Complaint channel and staff service), respectively. Except for these items, interviewees were dissatisfied with Item 2 (Convenience of finding a shared-bicycle, 43.0%), Item 4 (Deposit and withdraw, 43.0%), Item 9 (Convenience of carrying personal belongings), and Item 14 (Presence of slopes, 46.8%) the most. Although there are 8 items whose probability is less 50%, 80.3% of the interviewees overcame Item 1 (Overall satisfaction about the dockless BSS). Therefore, most of the interviewees were satisfied with service quality of the dockless BSS. Fig. 5

Since the academic qualifications and monthly consumption have significant influences on interviewees' ability, we divided interviewees according to academic qualifications and monthly consumption. In each subgroup, we analyzed the relationship between the interviewee's ability and the item's difficulty. Table 7 and Table 8 show the percentage of interviewees whose ability overcome the item's difficulty in the subgroup.

| Table 7 Percentage of interviewees whose ability overcomes the item's difficulty - grouped by education |

| Table 8 Percentage of students whose ability overcome the item's difficulty - grouped by monthly consumption |

Education has a significant impact on the relationship and on the difference between the interviewee's ability and the item's difficulty. For example, with regard to Item 2 (Convenience of finding a shared-bicycle), 65.4% of interviewees in the "High school or below" subgroup overcame the difficulty of Item 2, whereas only 37.6% of interviewees in the "Universities" subgroup overcame the difficulty of Item 2. In terms of Item 15 (Safety of the bicycle lane), 80.8% of the interviewees in the "High school or below" subgroup overcame the difficulty of Item 15. However, only 40.6% of the interviewees in the "Postgraduate" subgroup overcame this difficulty. In terms of Item 13 (Disturbance from pedestrians and cars), 57.7% and 26.6% of the interviewees in the "High school or below" subgroup and the "Universities" subgroup overcame the difficulty of Item 2, respectively.

The impact of monthly consumption of students on the relationship and on the difference between the interviewee's ability and the item's difficulty is remarkable, too. For example, 51.2% of the interviewees in the "< ¥1 000" subgroup overcame the difficulty of Item 2 (Convenience of finding a shared-bicycle), while only 34.6% of the interviewees in the "≥ ¥1 000" subgroup overcame the difficulty of Item 2. With regard to Item 13 (Disturbance from pedestrians and cars), 41.9% and 24.5% of the students in the "< ¥1 000" subgroup and the "≥ ¥1 000" subgroup overcame the difficulty of Item 13, respectively.

5 Discussions and Conclusions 5.1 Research FindingsIn this paper, we designed a questionnaire about service quality of the dockless BSS. The questionnaire contains 15 factors that affect service quality of the dockless BSS. Because users' evaluation of factors of service quality is just ordinal scales, they are not suitable for parametric analysis. Through the analysis of these raw data with Rasch Model, scale-free person parameters (ability) and sample-free item parameters (difficulty) were obtained. Users' ability and items' difficulty is interval scale and on the same unit. These interval data are more appropriate for further statistical analysis.

Through the analysis of interviewees' abilities, it is found that only education and monthly consumption have significant influence on interviewees' abilities. The average ability decreases with the increase in academic qualifications. Therefore, the lower a user's academic qualification is, the more satisfied the user is with the dockless BSS. Students whose monthly consumption are less than ¥1 000 are more satisfied than students whose monthly consumption are more than ¥1 000. However, gender, weekly use of dockless shared-bicycle, private car ownership, and monthly income have no significant influence on the interviewees' ability. Not all the result in this paper is consistent with previous findings.

As to items' difficulties, it is found that the four largest difficulties are Item 11 (Cycling under the adverse weather), Item 13 (Disturbance from pedestrians and cars, 0.75 logits), Item 12 (Continuity of the bicycle lane logits 0.59), and Item 16 (Complaint channel and staff service). On the other hand, Item 8 (Appearance of the shared-bicycle) has the smallest difficulty. Except for Item 8, the other simple items include Item 5 (Price), Item 3 (Convenience of unlocking a bicycle), and Item 7 (Comfort when cycling with the shared-bicycle).

In terms of comparison of ability and difficulty, it is found that less than 40% of interviewees overcame Item 11, Item 13, Item 12, and Item 16.

Through dividing interviewees into subgroups according to education and monthly consumption, it is found that the percentage of interviewees whose ability overcame the item's difficulty vary greatly among different subgroups. The impact of education on the differences between ability and difficulty is considerably large on Item 2, Item 4, Item 9, Item 14, and Item 15. For example, with regard to Item 15 (Safety of the bicycle lane), 80.80% of the interviewees in the "High school or below" subgroup overcame the difficulty of Item 15. At the same time, only 40.6% of interviewees in the "Postgraduate" subgroup overcame the difficulty of Item 15. The difference is 40.20%. The impact of monthly consumption of students on the relationship on the difference between the interviewee's ability and the item's difficulty is not so significant as the impact of education. The largest impact of monthly consumption is on Item 14 and Item 13.

5.2 Policy ImplicationsSince the dockless BSS plays an important role on the accessibility of the public transit, in order to promote mode split of the public transit, it is necessary to improve service quality of the dockless BSS.

Through the analysis in this paper, it is found that users of the dockless BSS were dissatisfied with cycling under the adverse weather the most. The weather condition is not pleasant in Guangzhou: it often rains, and the temperature is rather high in summer. The adverse weather in Guangzhou prevents lots of people from traveling by dockless shared bicycle. It also discourages people from traveling by public transit. Therefore, the relevant governmental department should pay attention to the influence of adverse weather. For example, more large-shade trees should be planted along the bicycle lane. When the trees have grown up, they will provide a comfortable cycling environment.

Except for cycling under the adverse weather, users were dissatisfied with disturbance from pedestrians and cars as well as continuity of the bicycle lane the most. These two items are related to conditions of the bicycle lane. It can be figured out that the bicycle lane condition is rather poor in Guangzhou, and much more effort should be made to improve service quality of the bicycle lane. For example, more bicycle lanes should be constructed, and the bicycle lane should be separated from cars and pedestrians. The government department should pay more attention to the planning of the bicycle lane in the urban planning.

5.3 Limitations and Future ResearchDifferent from travelers in Guangzhou, lots of people in small cities in China rely heavily on private cars, motorbikes, and private bicycles. The survey used in this paper was conducted only in Guangzhou. Since Guangzhou is the third largest city in China, the result in this paper may be unsuitable for other cities. Therefore, future studies should be made in small cities in China to compare the difference of evaluation between Guangzhou and small cities. Also, longitudinal analysis can also be performed to evaluate the effect of service improvement strategies. Furthermore, in this paper, we only investigated people who used the dockless shared bicycle, and we did not take into account travelers who did not use these bicycles. Further study can focus on these travelers' evaluation of dockless BSS.

Appendix

| Table A summary of literature involving the bicycle system |

| Table A summary of literature involving the bicycle system(Continued) |

| Table A summary of literature involving the bicycle system(Continued) |

| Table A summary of literature involving the bicycle system(Continued) |

| Table A summary of literature involving the bicycle system(Continued) |

| [1] |

Cheng Y-H, Chen S-Y. Perceived accessibility, mobility, and connectivity of public transportation systems. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 2015, 77: 386-403. DOI:10.1016/j.tra.2015.05.003 (  0) 0) |

| [2] |

Tyrinopoulos Y, Antoniou C. Public transit user satisfaction: Variability and policy implications. Transport Policy, 2008, 15(4): 260-272. DOI:10.1016/j.tranpol.2008.06.002 (  0) 0) |

| [3] |

Brons M, Givoni M, Rietveld P. Access to railway stations and its potential in increasing rail use. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 2009, 43(2): 136-149. DOI:10.1016/j.tra.2008.08.002 (  0) 0) |

| [4] |

Wan D, Kamga C, Liu J, et al. Rider perception of a "light" bus rapid transit system - The New York City select bus service. Transport Policy, 2016, 49: 41-55. DOI:10.1016/j.tranpol.2016.04.001 (  0) 0) |

| [5] |

Tilahun N, Thakuriah P, Li M, et al. Transit use and the work commute: Analyzing the role of last mile issues. Journal of Transport Geography, 2016, 54: 359-368. DOI:10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2016.06.021 (  0) 0) |

| [6] |

Rietveld P. The accessibility of railway stations: The role of the bicycle in the Netherlands. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment, 2000, 5(1): 71-75. DOI:10.1016/s1361-9209(99)00019-x (  0) 0) |

| [7] |

Murphy E, Usher J. The role of bicycle-sharing in the city: Analysis of the Irish experience. International Journal of Sustainable Transportation, 2014, 9(2): 116-125. DOI:10.1080/15568318.2012.748855 (  0) 0) |

| [8] |

Martens K. The bicycle as a feedering mode: Experiences from three European countries. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment, 2004, 9(4): 281-294. DOI:10.1016/j.trd.2004.02.005 (  0) 0) |

| [9] |

Martens K. Promoting bike-and-ride: The Dutch experience. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 2007, 41(4): 326-338. DOI:10.1016/j.tra.2006.09.010 (  0) 0) |

| [10] |

Ji Y, Fan Y, Ermagun A, et al. Public bicycle as a feeder mode to rail transit in China: The role of gender, age, income, trip purpose, and bicycle theft experience. International Journal of Sustainable Transportation, 2017, 11(4): 308-317. DOI:10.1080/15568318.2016.1253802 (  0) 0) |

| [11] |

Shaheen S A, Guzman S, Zhang H. Bikesharing in Europe, the Americas, and Asia: Past, present, and future. Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board, 2010, 2143(1): 159-167. DOI:10.3141/2143-20 (  0) 0) |

| [12] |

Fishman E. Bikeshare: A review of recent literature. Transport Reviews, 2015, 36(1): 92-113. DOI:10.1080/01441647.2015.1033036 (  0) 0) |

| [13] |

Carman J M. Consumer perceptions of service quality: An assessment of the servqual dimensions. Journal of Retailing, 1990, 66(1): 33-55. (  0) 0) |

| [14] |

Cheng Y-H, Liu K-C. Evaluating bicycle-transit users' perceptions of intermodal inconvenience. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 2012, 46(10): 1690-1706. DOI:10.1016/j.tra.2012.10.013 (  0) 0) |

| [15] |

Li Z, Wang W, Liu P, et al. Physical environments influencing bicyclists' perception of comfort on separated and on-street bicycle facilities. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment, 2012, 17(3): 256-261. DOI:10.1016/j.trd.2011.12.001 (  0) 0) |

| [16] |

Zhang T C, Bai S K, Chen S Y, et al. Evaluation of public bicycle system service quality based on revised SERVQUAL. Journal of Wuhan University of Technology (Transportation Science & Engineering), 2013(1): 216-220. DOI:10.3963/j.issn.2095-3844.2013.01.051 (  0) 0) |

| [17] |

Oh J S, Kim M S, Lee C H. A study on factors affecting the satisfaction of public bicycle system. International Journal of Highway Engineering, 2014, 16(2): 107-118. DOI:10.7855/IJHE.2014.16.2.107 (  0) 0) |

| [18] |

Jiang L Q, Wu B T. A research of people's satisfaction index about public bicycle system based on factor analysis —Take Wuxi as an example. Journal of Harbin University of Commerce, 2014(4): 73-80. (  0) 0) |

| [19] |

Calvey J C, Shackleton J P, Taylor M D, et al. Engineering condition assessment of cycling infrastructure: Cyclists' perceptions of satisfaction and comfort. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 2015, 78: 134-143. DOI:10.1016/j.tra.2015.04.031 (  0) 0) |

| [20] |

Zhang D, Xu X, Yang X. User satisfaction and its impacts on the use of a public bicycle system. Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board, 2015, 2512: 56-65. DOI:10.3141/2512-07 (  0) 0) |

| [21] |

Hopkins D, Mandic S. Perceptions of cycling among high school students and their parents. International Journal of Sustainable Transportation, 2016, 11(5): 342-356. DOI:10.1080/15568318.2016.1253803 (  0) 0) |

| [22] |

Bin L. The Research on Public Bicycle Satisfaction Evaluation by Fuzzy Comprehensive Evaluation.Xi'an: Chang'an University, 2016.

(  0) 0) |

| [23] |

Mengli L. Multi Level Fuzzy Comprehensive Evaluation in User Satisfaction of Public Bicycle System: A Case Study in Zhenjiang, Jiangsu. Zhenjiang: Jiangsu University, 2016.

(  0) 0) |

| [24] |

Manzi G, Saibene G. Are they telling the truth? Revealing hidden traits of satisfaction with a public bike-sharing service. International Journal of Sustainable Transportation, 2018, 12(8): 253-270. DOI:10.1080/15568318.2017.1353186 (  0) 0) |

| [25] |

Munkácsy A, Monzón A. Potential user profiles of innovative bike-sharing systems: The case of Bicimad (Madrid, Spain). Asian Transport Studies, 2017, 4(3): 621-638. DOI:10.11175/eastsats.4.621 (  0) 0) |

| [26] |

de Sousa A A, Sanches S P, Ferreira M A G. Perception of barriers for the use of bicycles. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 2014, 160: 304-313. DOI:10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.12.142 (  0) 0) |

| [27] |

Zhou Q. Study on the Characteristics of Public Bicycle as Means of Access/Egress for Metro and Subject Well-Being.Suzhou: Suzhou University, 2015.

(  0) 0) |

| [28] |

Fishman E, Washington S, Haworth N, et al. Factors influencing bike share membership: An analysis of Melbourne and Brisbane. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 2015, 71: 17-30. DOI:10.1016/j.tra.2014.10.021 (  0) 0) |

| [29] |

Bachand-Marleau J, Lee B H Y, El-Geneidy A M. Better understanding of factors influencing likelihood of using shared bicycle systems and frequency of use. Transportation Research Record, 2012, 2314(2314): 66-71. DOI:10.3141/2314-09 (  0) 0) |

| [30] |

Fernández-Heredia Á, Monzón A, Jara-Díaz S. Understanding cyclists' perceptions, keys for a successful bicycle promotion. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 2014, 63: 1-11. DOI:10.1016/j.tra.2014.02.013 (  0) 0) |

| [31] |

Kaplan S, Manca F, Nielsen T A S, et al. Intentions to use bike-sharing for holiday cycling: An application of the theory of planned behavior. Tourism Management, 2015, 47: 34-46. DOI:10.1016/j.tourman.2014.08.017 (  0) 0) |

| [32] |

El-Assi W, Mahmoud M S, Habib K N. Effects of built environment and weather on bike sharing demand: A station level analysis of commercial bike sharing in Toronto. Transportation, 2017, 44(3): 589-613. DOI:10.1007/s11116-015-9669-z (  0) 0) |

| [33] |

Zhao P, Li S. Bicycle-metro integration in a growing city: The determinants of cycling as a transfer mode in metro station areas in Beijing. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 2017, 99: 46-60. DOI:10.1016/j.tra.2017.03.003 (  0) 0) |

| [34] |

Bilder C R, Loughin T M. Analysis of Categorical Data with R. Boca Raton: CRC Press, 2014.

(  0) 0) |

| [35] |

Yanqin O. An empirical study on the satisfaction of urban residents using public bicycle travel.Nanchang: Jiangxi Normal University, 2016.

(  0) 0) |

| [36] |

Hawkins R J, Kremer M J, Swanson B, et al. Use of the Rasch model for initial testing of fit statistics and rating scale diagnosis for a general anesthesia satisfaction questionnaire. Journal of Nursing Measurement, 2014, 22(3): 381-403. DOI:10.1891/1061-3749.22.3.381 (  0) 0) |

| [37] |

Linacre J M. Optimizing rating scale category effectiveness. Journal of Applied Measurement, 2002, 3(1): 85-106. (  0) 0) |

| [38] |

Boone W J, Staver J R, Yale M S. Rasch analysis in the human sciences. Springer, 2014. DOI:10.1007/978-94-007-6857-4 (  0) 0) |

| [39] |

Pucher J, Buehler R. Integrating bicycling and public transport in north America. Journal of Public Transportation, 2009, 12(3): 79-104. DOI:10.5038/2375-0901.12.3.5 (  0) 0) |

| [40] |

Krizek K J, Stonebraker E W. Assessing options to enhance bicycle and transit integration. Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board, 2011, 2217: 162-167. DOI:10.3141/2217-20 (  0) 0) |

| [41] |

Liu L, Li Y, Xu G. Empirical study of bike sharing service satisfactions in Wuhan city. Logistics Engineering and Management, 2011(5): 116-117. (  0) 0) |

| [42] |

Huang C, Zou Zhi-Yun. People's intention towards public bicycle system in Wuhan. Proceedings of 2015 8th International Symposium on Computational Intelligence and Design (Iscid).Piscataway: IEEE, 2015.148-151. DOI: 10.1109/ISCID.2015.188. http://www.researchgate.net/publication/304549729_People's_Intention_towards_Public_Bicycle_System_in_Wuhan

(  0) 0) |

| [43] |

Lin J-J, Wang N-L, Feng C-M. Public bike system pricing and usage in Taipei. International Journal of Sustainable Transportation, 2017, 11(9): 633-641. DOI:10.1080/15568318.2017.1301601 (  0) 0) |

| [44] |

Mattson J, Godavarthy R. Bike share in Fargo, North Dakota: Keys to success and factors affecting ridership. Sustainable Cities and Society, 2017, 34: 174-182. DOI:10.1016/j.scs.2017.07.001 (  0) 0) |

| [45] |

Zhang Y, Thomas T, Brussel M, et al. Exploring the impact of built environment factors on the use of public bikes at bike stations: Case study in Zhongshan, China. Journal of Transport Geography, 2017, 58: 59-70. DOI:10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2016.11.014 (  0) 0) |

2020, Vol. 27

2020, Vol. 27