2. A.V. Topchiev Institute of Petrochemical Synthesis RAS, Moscow 119991, Russian Federation

Plastic waste occupies one of the top places in the composition of municipal solid waste. The share of plastics in municipal waste is steadily increasing every year. Today, approximately 150 types of various plastics are produced. Standard thermoplastics, such as low and high-pressure polyethylene (LDPE and LDPE), polypropylene (PP), polystyrene (PS), polyvinyl chloride (PVC), account for about 80% of the produced polymers[1].

Nowadays, special attention is paid to the problem of utilization and recycling of plastic waste, which is associated with several aspects. Because of high quantity of plastic wastes and their high inertness in the environment, these wastes are accumulated in special disposal places, which negatively affect ecological situation. On the other hand, polymer wastes are valuable materials suitable for being processed into various hydrocarbon products, such as synthetic liquid motor fuels and petrochemical raw materials[2].

The most effective and environmentally safe technologies for the processing of polymeric materials are represented by thermal and thermocatalytic cracking. However, thermal cracking has a significant disadvantage, for erample distilled products obtained as a result of thermal degradation have a paraffin base, which does not allow their use as motor fuels without preliminary refinement by reforming, isomerisation and other catalytic processes[3]. Such treatment increases the cost of final products and makes it problematic to use thermal cracking on industrial scale.

The thermocatalytic cracking technology is devoid of this disadvantage. Therefore, at present works, aimed at selecting optimal types of catalysts and technological modes of their application, are actively carried out. Among polymer cracking catalysts, various forms of zeolites have received the most attention due to their high catalytic activity and the possibility to control the cracking depth by varying the silicate modulus (acidity) of the zeolite[4-18].

However, with all their advantages, high-performance synthetic zeolite catalysts are expensive in manufacturing (by hydrothermal synthesis), and quickly lose their activity due to excessive coke formation in the pores and on the surface of the catalyst, which leads to the need for frequent and rather expensive process of their regeneration.In this connection, it is of interest to search for new, cheaper and more efficient catalysts for polymer cracking that will retain their activity for longer time.

In our previous work[19], it was shown that partially protonated PPT is a promising catalyst for thermal cracking of polysterene. This product is a quasi-amorphous material, which has a layered structure formed by double layers of TiO6/2 octahedra with K+ and H3O+ cations placed among them. High specific surface area of the parent PPT (up to 200 m2/g) and relatively large interlayer distance in these particles make this material promising for acting as a catalyst for the cracking of other types of polymers.

In this regard, the aim of this study is to investigate the possibility to apply PPT as a catalyst for cracking the polyolefins, for example using polypropylene, in comparison with zeolite catalyst CBV-780, is most widely used for these purposes. The main attention is directed at revealing the differences in catalytic action of the investigated materials, as well as the influence of the lifetime of these catalysts on their catalytic activity.

1 Materials and ExperimentGranulated polypropylene of H030GP grade (Sibur, Russia) was used as feedstock for thermal and thermocatalytic cracking. Zeolite CBV-780 (Zeolyst Int., USA) and PPT, synthesized by thermal treatment (500 ℃, 2 h) with a mixture of TiO2, KOH and KNO3 powder (weight ratio TiO2∶KOH∶KNO3 = 30∶30∶40) in accordance with Ref.[20], was used as catalysts. The PPT type (synthesis conditions) was chosen considering the results of earlier research [21], which showed the highest activity as a catalyst in the polypropylene thermal degradation process. Thermal and catalytic decomposition of polypropylene was carried out, using the stainless-steel reactor (0.5 dm3)[19], which allows cracking the polymers under controlled isothermal conditions.

Polymer granules or their mixtures with various powdered catalysts (10% of the total weight of the loading, average size is of 10 μm) were placed in the reactor. After that, the reactor was cleaned from air and filled with inert gas (N2, GOST 9293-74, 99.9% purity) at a rate of 50 mL/min, which made it possible to exclude the process of thermo-oxidative degradation of the polymer during thermal treatment. After blowing with a fivefold volume of gas, the reactor content was heated at a rate of 20 ℃ per minute until the temperature reached 450 ℃. After that, the reactor was kept at this temperature until the polymer decomposition process was completed. The time elapsed from the start of heating the reactor contents to the cessation of outgassing caused by polymer decomposition was recorded as the time of the cracking process. After that, the heating was stopped, and the reactor was cooled down to room temperature in a natural way.

The products, formed as a result of cracking in the form of gas-vapor phase, were directed to the reverse water cooler, where condensation of heavy hydrocarbon components was carried out. The obtained liquid phase was collected in the trap-receiver, whereas light (gaseous) products were collected in the gas meter.

The resulting distilled cracking products were analyzed by the gas-vapor chromatography-mass spectrometry method. A PegasusⓇ BT 4D chromatography-mass spectrometer (Leco, USA) equipped with an Agilent 7890A gas chromatograph (Agilent Technologies, USA), an integrated furnace and a FLUXTM flow modulation system were applied. A combination of a Restek Rxi-17Sil MS medium-polar column (30 m, ID 0.25 mm, film thickness 0.25 μm) and a Restek Rxi-5Sil MS non-polar column (2 m, ID 0.1 mm, film thickness 0.1 μm) was used to separate the hydrocarbons in the flow of helium at 1.5 mL/min.

Data acquisition and processing were performed using ChromaTOF software (version 5.51, Leco, USA). Individual peaks were identified automatically, based on a signal-to-noise (S/N) ratio of 50∶1 for automatic group analysis and 500∶1 for manual component identification. The compounds were identified by reference standards, retention times, elution order, NIST21 mass spectral database and mass spectrum fragmentation schemes.Solid residues of thermal and thermocatalytic cracking (coke or its mixture with catalyst powder) were removed from the reactor, weighed and analyzed using the Rock-EvalⓇ pyrolytic method according to the procedure described in our previous work[21]. The analysis was carried out with a Rock-Eval 6 Turbo instrument (Vinci Technologies, France), in which a sample of the solid material under study was placed in a pyrolysis furnace, blown with a flow of inert gas (Ar), and then in an afterburning furnace in air atmosphere.

A Quantachrome NOVA 1000e analyzer was used to measure a specific surface area of the PPT catalyst.

2 Results and DiscussionThe time required for complete decomposition of polypropylene at 450 ℃, as well as the yield of products obtained during thermal and thermocatalytic (using different catalysts) cracking, are presented in Table 1. In the table, n represents the number of the cycle at the catalytic cracking.

| Table 1 Yield of the products of thermal and thermocatalytic cracking of polypropylene in the studied systems |

The results obtained confirm that both types of the studied catalysts can significantly accelerate the polymer destruction process. When the catalysts were first used, their effect on the PP destruction rate was approximately the same. However, the zeolite catalyst (CBV-780) significantly reduced its catalytic activity in the tenth cycle of use (the time required to complete the cracking process increased by 1.4 times), whereas in the case of PPT, no noticeable change in the process rate was observed. PPT only slightly reduced its catalytic activity during the tenth cycle of use. The amount of coke increased by only 1.2 wt.%, and the yield of distilled (liquid) products did not change. Moreover, the total yield of liquid products in the studied catalytic processes is close to the data noted in the literature for other types of PP cracking catalysts[2, 8, 22, 23].

At the first use, the catalytic activity of the traditional polymer cracking catalyst CBV-780 was higher than that obtained with PPT (time of the total decomposition was 44 and 53 min, respectively). However, its multiple (10 times) uses led to a significant loss of catalytic activity (time of the total decomposition increased from 44 to 62 min), whereas this characteristic practically did not changed for the PPT catalysts. Furthermore, undecomposed coke residue for the CBV-780 increased by 5.2 wt.%, whereasa quantity of solid product increased only by 1 wt.% in the case of PPT.

To evaluate the nature of the processes occurring on the surface of the investigated catalysts during the cracking process and leading to the loss of their catalytic action, hydrogen indices of the formed solid residues were determined using the Rock-Eval method. The coke residues of thermocatalytic degradation represented the mixtures of spent catalysts and solid carbonized products. The data on hydrogen indices of the obtained samples of solid residues are reported in Table 2 in terms of hydrocarbon mass in the solid residue.

| Table 2 Hydrogen indices of solid residues obtained using various catalysts in the processes of thermal and thermocatalytic degradation of PP |

The maximum amount of hydrocarbon compounds (628 mg HC per 1 g of coke) in the solid residue was formed during the PP thermal cracking. A part of solid products could be formed on the reactor walls as a result of indirect reactions of polycondensation of high-boiling products and following delamination and falling into the polymer melt[24-25]. This component remains constant in all conducted experiments and is determined by the geometrical parameters of the reactor and the temperature regime of its operation. Another part of solid cracking products is formed directly on the surface of the catalyst and eventually leads to blocking its active catalytic centers.

According to Table 2, the solid product formed as a result of the thermocatalytic degradation of PP in the presence of PPT, even after the first use, has a lower hydrogen index than the solid residue obtained using zeolite catalyst (89 and 130, respectively). With multiple application of the investigated catalysts, hydrogen index of solid products slightly increased, but, at the same time, remained lower for products obtained with PPT than in the case of zeolite catalyst. This indicates that the composition of cracking residues formed during PP degradation in the presence of PPT contains a smaller amount of compounds with hydrogenated carbon atoms. In other words, these residues have relatively low resin contents and contain predominantly amorphous carbon.

Thus, considering the nature of cracking residues, potassium polititanate is a catalyst less prone to form coke residues. The solid residue is mostly porous amorphous carbon, which blocks active centers of the catalyst surface to a lesser extent in comparison with the resin-like residues forming on the surface of CBV-780. The composition of gaseous products of the thermal and thermocatalytic degradation of PP in the presence of PPT and CBV-780 is reported in Table 3.In the table, n represents the number of cracking cycles.

| Table 3 Chemical composition of the gaseous products obtained by the thermal and thermocatalytic cracking of PP in the presence of various catalysts |

Considering composition of the gaseous products obtained with thermal and thermocatalytic cracking of polypropylene, it is necessary to take into account that the investigated reaction system consists of two phases (vapor/gaseous and liquid/molten), in which decomposition processes could take place. One part of gaseous products is formed as a result of thermal cracking of hydrocarbon vapors represented in the gas-vapor part of the reactor, whereas another part appears to be the result of thermocatalytic cracking with participation of the catalysts, occurring in the liquid phase (molten PP and hydrocarbon products with a boiling point above 450 ℃)

It could be expected that the composition of the products, formed as a result of thermal cracking of hydrocarbons in the vapor phase, does not have big differences in the presence of different catalysts in the molten polypropylene. Therefore, any changes in the composition of gaseous products observed in the presence of catalysts indicate a significant change in the mechanism of polymer cracking processes in the liquid phase (thermocatalytic process).

The data of Table 3 show that the gaseous product of thermal cracking of PP is mainly enriched with propylene (56.5 wt.%), ethane (13.0 wt.%), isobutylene (8.6 wt.%), methane (6.1 wt.%) and n-pentane (6.0 wt.%).A difference between the chemical composition of gaseous products obtained with PPT and CBV-780 catalysts indicates different mechanism of their catalytic action.

The composition of gaseous product of the PP thermocatalytic cracking in the presence of PPT is enriched with methane, ethane and propylene, which is the similar to the case of thermal cracking. This fact indicates that, in the systems based on molten PP and molten PP containing PPT particles, the gaseous products preferably are formed in the gas-vapor phase. It is possible to propose that introducing the PPT particles into the molten polymer promoted formation of the products with a boiling point lower than 450 ℃. We can assume that these products, formed under the action of PPT, are not strongly connected to a surface of the catalyst, since they can be easily desorbed, passing from the polymer melt into the gas-vapor phase and decomposing there because of a radical-chain mechanism[2, 26]. As a result, compositions of the gaseous products obtained with the thermal and PPT-catalyzed cracking do not have significant differences. A presence of PPT only accelerates the decomposition of long-chain olefins in the molten PP.

On the other hand, introducing the zeolite catalyst (CBV-780) into the PP melt significantly changes the composition of gaseous cracking product; n-butane and isobutane become the main products, whereas proportions of propylene, CH4 and C2H6, sharply decreases. This fact indicates that, in comparison with PPT, the introduction of zeolite into the PP melt leads to a more significant change in the mechanism of polymer degradation processes taking place in the melt.

During the first cycle of the catalyst application, the cracking of PP in the liquid phase is accompanied with a high rate of the gaseous hydrocarbons formation, as shown in Table 1. However, the composition of these products differs from the one obtained in the catalysts free thermal cracking, it is possible to note the presence of a large amount of n-butane (43.9%), which is not formed at the PP thermal cracking (0.9%). Such composition of gaseous products is typical for catalytic cracking of polyolefins, which occurs via a cationic mechanism[27-28]. The long-chain olefins, formed in the initial stages of the thermal cracking and further adsorbed onto the surface of catalysts, are protonated under acidic conditions to form Cn+ cations, which is then directly cleaved to form light olefins.

At the tenth cycle of use, the composition of gaseous products of PP cracking using PPT (yield of CH4, C2Н6, С3Н6, i-C4H8) gradually approaches the composition of thermal cracking products. However, a much more significant convergence of this data is observed in the case of multiple use of zeolite catalyst CBV-780. We can note a big yield of C3H6 (increased from 0.4 to 39.2 wt. %), which is typical for thermal cracking, along with intensively increased yield of i-C4H8 (from 8.8 to 21.6 wt.%). Thus, we could propose the presence of two effects.

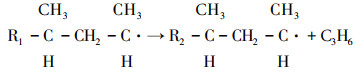

1) Increased contribution of the processes characteristic of non-catalytic thermal cracking and associated with the decomposition of primary and secondary hydrocarbon radicals:

|

(1) |

|

(2) |

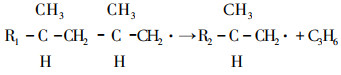

2) Increased role of the processes associated with decomposition of tertiary radicals:

|

(3) |

Since reaction (3) is not characteristic of thermal cracking, it can be assumed that changes in the zeolite catalyst operation are related not only to the blocking of active catalytic centers on the zeolite surface, but to the changes in the structure of these centers. The nature of this effect requires a more detailed investigation. We can only propose that the formation of a large number of tertiary hydrocarbon radicals is related to more intensive interaction of free radicals with the hydrogen atoms of the end groups of hydrocarbons adsorbed on the surface of multiply used zeolite catalyst.

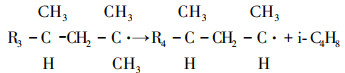

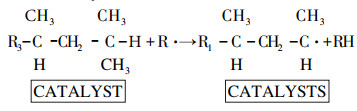

|

(4) |

This effect can also be associated with an increase in the intensity of catalytic reactions causing the formation of branched-chain hydrocarbons (isomerization). The compositions of distilled (liquid) products obtained as a result of thermal and thermocatalytic destructions are reported in Table 4.

| Table 4 Compositions of liquid products of thermal and thermocatalytic degradation of polypropylene |

Considering the data on analysis of the distilled (liquid) products, as shown in Table 4, we can note that the mixture of liquid hydrocarbons obtained as a result of thermal destruction has a higher molecular weight of the components and is mainly enriched with hydrocarbons of olefin series. The total content of olefins is 84.6 wt.%, naphthenes account for 8.8 wt.%, isoparaffins and paraffins are 3.1 and 3.7 wt.%, respectively.

When PPT is used as a catalyst, the rate of cracking increases and there is a general decrease in the molecularity of liquid hydrocarbon products. This is especially noticeable for olefins; Compared to thermal cracking, the content of components C10+ decreased by 7.9 wt.%. The influence of the catalyst is also evidenced by the appearance of aromatic compounds in the distillate (0.9 wt.%), as well as an increase in the yield of naphthenes (by 1.3 wt.%).

Zeolite catalyst, as well as PPT, allows producing relatively low molecular weight distillate, but there is a more significant change in its qualitative composition. The product obtained in the presence of CBV-780, in comparison with thermal cracking, contains significantly less naphthenic and olefinic hydrocarbons (by 8.0 and 6.0 wt.%, respectively). At the same time, the content of iso-paraffins and paraffins increases significantly (by 5.4 and 4.8 wt.%, respectively). The yield of aromatic components also increases by 3.9 wt.%. As a result of the tenfold use of PPT as a catalyst (without regeneration), an increase in the content of olefinic (by 11.7 wt.%) and paraffinic (by 2.7 wt.%) hydrocarbons is observed in the liquid product. However the amount of naphthenes sharply decreases by 10.0 wt.%. At the same time iso-paraffin hydrocarbons disappear from the distillate (3.7 wt.% decrease). In the case of multiple application of zeolite catalyst CBV-780, the yield of iso-paraffin and paraffin hydrocarbons significantly decreases (by 5.2 and 4.3 wt.% respectively).Moveover, There is also a slight decrease in the content of aromatic and naphthenic components. At the same time, in contrast to the case of PPT use, under the action of CBV-780, the yield of olefins increased by 10.9 wt.%. However, even after the tenth use, the distillate product obtained in the presence of zeolite catalyst remains lighter in comparison with the similar product of thermocatalytic cracking in the presence of PPT.

Qualitative and quantitative analysis of the chemical composition of the products, obtained in the presence of conventional and new catalysts, confirm that the PP cracking in the presence of potassium polytitanate (PPT) and zeolite catalyst CBV-780 proceeds in different ways. On the other hand, compared to thermal cracking, the action of PPT introduces less significant changes in the composition of liquid products in comparison with the action of CBV-780. At the same time, cracking of PP in the presence of PPT particles, in comparison with thermal cracking, is characterized by the acceleration of the decomposition processes of hydrocarbons adsorbed on the catalyst surface.

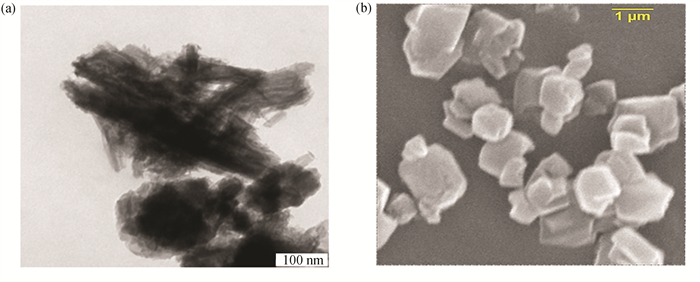

To explain the regularities of the PP thermocatalytic cracking in the presence of CBV-780 and PPT, we have to consider some structural features of these catalysts, as shown in Fig. 1. In Fig. 1, images of the PPT and CBV-780 particles have been obtained with TEM Carl Zeiss Libra (PPT) and SEM ASPEX Explorer (zeolite).The CBV-780 zeolite particles have irregular quasi-spherical shape, whereas the multilayer PPT particles are formed by quasi-two-dimension platelets. At the same time, in the zeolite particles the external window-like pores have a diameter of about 7.5 nm[27, 29], while the PPT particles, formed by layers of TiO6 octahedra, present flat-like pores with an interlayer distance (gap) varied in the range of 0.2-1.1 nm[19-21].

|

Fig.1 Images of (a) the PPT particles and (b) the CBV-780 particles |

Generally, the main characteristics, influencing catalytic action in the cracking process, are related to the acidity and shape of the particles[26-28]. Furthermore, it is known that the acidity of various mixed oxides depends on the molar ratio of [M4+]/[M3+] in their structure. A high catalytic activity of the protonated forms of mixed oxides, used in this research, can be determined by high concentration of the Lewis and Brønsted active centers. Some structural features of the catalysts are reported in Table 5 and can be taken into account to propose that the acidity of these powders has the same nature. The [Si4+]/[Al3+] and [Ti4+]/[Ti3+] molar ratios in these catalysts are close (54 and 47, respectively)[27, 29].

Therefore, the other structural features (morphology, surface area, pore size and pore volume) of CBV-780 and PPT particles, as demonstrated in Fig. 1 and Table 5, should be considered more carefully.

| Table 5 Structural characteristics of the CBV-780 and PPT catalysts (in accordance with Refs.[27, 29, 20, 30]) |

The PPT powder has lower specific surface area compared to CBV-780 (238 and 756 m2/g, respectively). However, it is known that the presence of well-developed micropores in zeolites can limit the diffusion of reactants (products) and catalytic action[28, 29, 31]. Large size of polymer molecules, as well as the products of primary (thermal) cracking in the melt, make their treatment difficult by microporous zeolites using their internal surface. It was noted earlier[32] that the lowest liquid oil yield and highest gas production in catalytic pyrolysis with synthetic zeolites can be due to their microporous structure and high BET surface area, promoting decomposition of relatively light C10-C15 hydrocarbons (intermediate products of pyrolysis). However, formation of coke onto the external surface of zeolites can block the channels connecting internal micropores (up to 7.5 nm in diameter) with the zeolite surface (window-like micropers onto the external surface of particles, 0.74 nm in diameter). At the same time, it is significantly more difficult to block flat-like pores of the PPT particles with pyrolysis products (coke).

3 Conclusions1) PPT can be considered as a new promising catalyst intended for thermocatalytic cracking of polyolefins.

2) The use of PPT-based catalyst increases the yield of liquid products of polypropylene (PP) wastes cracking compared to thermal cracking and thermocatalytic cracking under the action of CBV-780.

3) The PPT catalytic action mechanism in the cracking process differs from the one for the PP cracking in the presence of zeolites (i.e. CBV-780). This difference is confirmed by the chemical composition of both gaseous and liquid products of thermocatalytic cracking.

4) The chemical composition of the PP cracking products in the presence of PPT is closer to the composition of thermal cracking products, and obtained catalytic effect is related to the increase in the rate of decomposition process of intermediate products adsorbed onto the PPT surface. Relatively quick desorption of the C10-C15 cracking products from the PPT surface provides low rate of coke deposits formation and possibility of multiple cycle application without changes in the rate of the PP decomposition and chemical composition of the products obtained by cracking. At the same time, this effect promotes increased content of liquid products (oil) of cracking characterized with relatively low temperature of boiling.

5) In the first use, the zeolite catalyst promote more completed decomposition and increased yield of gaseous and light liquid hydrocarbons in comparison with PPT due to a higher affinity of the adsorbed intermediate products with the surface. However, this feature contributes to a more intense formation of coke deposits and reduced catalytic action after multiple using.

| [1] |

Okan M, Aydin H M, Barsbay M. Current approaches to waste polymer utilization and minimization: A review. Journal of Chemical Technology & Biotechnology, 2019, 94(1): 8-21. DOI:10.1002/jctb.5778 (  0) 0) |

| [2] |

Hájeková E, Špodová L, Bajus M, et al. Separation and characterization of products from thermal cracking of individual and mixed polyalkenes. Chemical Papers, 2007, 61: 262-270. DOI:10.2478/s11696-007-0031-6 (  0) 0) |

| [3] |

Miller S J, Shah N, Huffman G P. Conversion of waste plastic to lubricating base oil. Energy and Fuels, 2005, 19: 1580-1586. DOI:10.1021/ef049696y (  0) 0) |

| [4] |

Lopez A, Marco I D, Caballero B M, et al. Catalytic pyrolysis of plastic wastes with two different types of catalytic: ZSM-5 zeolite and Red Mud. Applied Catalysis B: Environment and Energy, 2011, 104: 211-219. DOI:10.1016/j.apcatb.2011.03.030 (  0) 0) |

| [5] |

Artetxe M, Lopez G, Amutio M, et al. Cracking of high density polyethylene pyrolysis waxes on HZSM-5 catalysts of different acidity. Industrial and Engineering Chemistry Research, 2013, 52: 10637-10645. DOI:10.1021/ie4014869 (  0) 0) |

| [6] |

Marcilla A, Beltran M I, Navarro R. Thermal and catalytic pyrolysis of polyethylene over HZSM-5 and HUSY zeolites in a batch reactor under dynamic conditions. Applied Catalysis B: Environment and Energy, 2009, 86: 78-86. DOI:10.1016/j.apcatb.2008.07.026 (  0) 0) |

| [7] |

Serrano D P, Aguado J, Escola J M, et al. Nanocrystalline ZSM-5: A highly active catalyst for polyolefin feedstock recycling. Studies in Surface Science and Catalysis, 2002, 142: 77-84. DOI:10.1016/s0167-2991(02)80014-3 (  0) 0) |

| [8] |

Serrano D P, Aguado J, Escola J M, et al. Influence of nanocrystalline HZSM-5 external surface on the catalytic cracking of polyolefins. Journal of Analytical and Applied Pyrolysis, 2005, 74: 353-360. DOI:10.1016/j.jaap.2004.11.037 (  0) 0) |

| [9] |

Aguado J, Serrano D P, Escola J M, et al. Catalytic conversion of polyolefins into fuels over zeolite beta. Polymer Degradation and Stability, 2000, 69: 11-16. DOI:10.1016/s0141-3910(00)00023-9 (  0) 0) |

| [10] |

Elordi G, Olazar M, Lopez G, et al. Role of pore structure in the deactivation of zeolites (HZSM-5, H-β and HY) by coke in the pyrolysis of polyethylene in a conical spouted bed reactor. Applied Catalysis B: Environment and Energy, 2011, 102: 224-231. DOI:10.1016/j.apcatb.2010.12.002 (  0) 0) |

| [11] |

Elordi G, Olazar M, Artetxe M, et al. Effect of the acidity of the HZSM-5 zeolite catalyst on the cracking of high density polyethylene in a conical spouted bed reactor. Applied Catalysis A: General, 2012, 415(416): 89-95. DOI:10.1016/j.apcata.2011.12.011 (  0) 0) |

| [12] |

Artetxe M, Lopez G, Amutio M, et al. Light olefins from HDPE cracking in a two-step thermal and catalytic process. Chemical Engineering Journal, 2012, 207(208): 27-34. DOI:10.1016/j.cej.2012.06.105 (  0) 0) |

| [13] |

Ibanez M, Artetxe M, Lopez G, et al. Identification of the coke deposited on an HZSM-5 zeolite catalyst during the sequenced pyrolysis-cracking of HDPE. Applied Catalysis B: Environment and Energy, 2014, 148(149): 436-445. DOI:10.1016/j.apcatb.2013.11.023 (  0) 0) |

| [14] |

Aguado J, Serrano D P, Escola J M, et al. Catalytic cracking of polyethylene over zeolite mordenite with enhanced textural properties. Journal of Analytical and Applied Pyrolysis, 2009, 85: 352-358. DOI:10.1016/j.jaap.2008.10.009 (  0) 0) |

| [15] |

Caldeira V P S, Peral A, Linares M, et al. Properties of hierarchical Beta zeolites prepared from protozeolitic nanounits for the catalytic cracking of high density polyethylene. Applied Catalysis A: General, 2017, 531: 187-196. DOI:10.1016/j.apcata.2016.11.003 (  0) 0) |

| [16] |

Santos B P S, Almeida D, Marques M F V, et al. Petrochemical feedstock from pyrolysis of waste polyethylene and polypropylene using different catalysts. Fuel, 2018, 215: 515-521. DOI:10.1016/j.fuel.2017.11.104 (  0) 0) |

| [17] |

Lin X, Zhang D, Ren X, et al. Catalytic co-pyrolysis of waste corn stover and high-density polyethylene for hydrocarbon production: The coupling effect of potassium and HZSM-5 zeolite. Journal of Analytical and Applied Pyrolysis, 2020, 150: 104895. DOI:10.1016/j.jaap.2020.104895 (  0) 0) |

| [18] |

Rehan M, Miandad R, Barakat M A, et al. Effect of zeolite catalysts on pyrolysis liquid oil. International Biodeterioration and Biodegradation, 2017, 119: 162-175. DOI:10.1016/j.ibiod.2016.11.015 (  0) 0) |

| [19] |

Zherdetsky N A, Gorokhovsky A V. Thermocatalytic destruction of polystyrene in the presence of potassium polytitanate. ChemChemTech, 2023, 66(3): 77-84. DOI:10.6060/ivkkt.20236603.6759 (  0) 0) |

| [20] |

Sanchez-Monjaras T, Gorokhovsky A, Escalante-Garcia J I. Molten salt synthesis and characterization of potassium polytitanate ceramic precursors with varied TiO2/K2O molar ratios. Journal of the American Ceramic Society, 2008, 91(9): 3058-3065. DOI:10.1111/j.1551-2916.2008.02574.x (  0) 0) |

| [21] |

Zherdetsky N A, Gorokhovsky A V. Application of pyrolytic method Rock-Eval for estimation of catalytic activity of modified potassium polytitanates at polypropylene degradation. International Research Journals, 2022, 120(6-1): 32-35. DOI:10.23670/IRJ.2022.120.6.006 (  0) 0) |

| [22] |

Furda L V, Smalchenko D E, Titov E N, et al. Thermocatalytic degradation of polypropylene in presence of aluminum silicates. ChemChemTech, 2020, 63(6): 85-89. DOI:10.6060/ivkkt.20206306.6202 (  0) 0) |

| [23] |

Stelmachowski M, Słowiński K. Thermal and thermo-catalytic conversion of waste polyolefins to fuel-like mixture of hydrocarbons. Chemical and Process Engineering, 2012, 33(1): 185-198. DOI:10.2478/v10176-012-0016-z (  0) 0) |

| [24] |

Mohamadalizadeh A, Towfighi J, Karimzadeh R. Modeling of catalytic coke formation in thermal cracking reactors. Journal of Analytical and Applied Pyrolysis, 2008, 82(1): 134-139. DOI:10.1016/j.jaap.2008.02.006 (  0) 0) |

| [25] |

Symoens S H, Olahova N, Muñoz Gandarillas A E, et al. State-of-the-art of coke formation during steam cracking: Anti-coking surface technologies. Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research, 2018, 57(48): 16117-16136. DOI:10.1021/acs.iecr.8b03221 (  0) 0) |

| [26] |

He Y, Li H, Xiao X, et al. Polymer degradation: Category, mechanism and development prospect. E3S Web of Conferences. Les Ulis: EDP Sciences, 2021, 290: 01012. DOI:10.21203/rs.3.rs-211010/v1 (  0) 0) |

| [27] |

Milato J V, França R J, Marques M R C. Pyrolysis of oil sludge from the offshore petroleum industry: Influence of different mesoporous zeolites catalysts to obtain paraffinic products. Environmental Technology, 2021, 42(7): 1013-1022. DOI:10.1080/09593330.2019.1650833 (  0) 0) |

| [28] |

Wang Y, Yokoi T, Namba S, et al. Improvement of catalytic performance of MCM-22 in the cracking of n-hexane by controlling the acidic property. Journal of Catalysis, 2016, 333: 17-28. DOI:10.1016/j.jcat.2015.10.011 (  0) 0) |

| [29] |

Corma A. State of the art and future challenges of zeolites as catalysts. Journal of Catalysis, 2003, 216(1-2): 298-312. DOI:10.1016/S0021-9517(02)00132-X (  0) 0) |

| [30] |

Gorokhovsky A, Morozova N, Yurkov G, et al. Catalytic decomposition of H2O2 in the aqueous dispersions of the potassium polytitanates produced in different conditions of molten salt synthesis. Molecules, 2023, 28(13): 4945. DOI:10.3390/molecules28134945 (  0) 0) |

| [31] |

Yu Y, Li X, Su L, et al. The role of shape selectivity in catalytic fast pyrolysis of lignin with zeolite catalysts. Applied Catalysis A, 2012, 447-448: 115-123. DOI:10.1016/j.apcata.2012.09.012 (  0) 0) |

| [32] |

Seo Y H, Lee K H, Shin D H. Investigation of catalytic degradation of high density, polyethylene by hydrocarbon group type analysis. Journal of Analytical and Applied Pyrolysis, 2003, 70: 383-98. DOI:10.1016/S0165-2370(02)00186-9 (  0) 0) |

2025, Vol. 32

2025, Vol. 32