苯胺及其衍生物是重要的有机化工原料,广泛应用于医药、染料、农药和军工等领域[1-5]。当人体接触到苯胺时,苯胺会进入人体导致有机组织缺氧,损伤内脏器官。同时,苯胺也是一种潜在的致癌物,对人体健康构成严重威胁[6-9]。由于工业废水的不合格排放,苯胺经常存在于河湖水环境和地表水中,造成一系列严重的环境污染。由于苯胺类污染物具有很强的生物毒性,且存在于高酸、高碱的复杂盐体系中,传统的废水净化技术,如物理吸附[10]、萃取[11]、膜分离[12]、微生物[13]分解等方法,均无法有效去除[14-15]。光催化技术作为一种取之不尽、用之不竭的太阳能技术,具有循环绿色可持续发展的特点,逐渐成为处理水中各种有机污染物的一种更为有效的环境生态修复方式[16-17]。

基于半导体的光催化技术已被证明是一种前沿的环境净化方法。在众多光催化剂中,二氧化钛因其无毒、低成本、高稳定性和优异的光活性而被认为是最有前途的光催化材料之一[18-20]。目前,P25 TiO2作为最知名的商用纳米半导体光催化剂,表现出比大多数报道的其他纳米结构光催化剂更好的光催化活性。这归因于组成P25的锐钛矿与金红石之间的界面电子转移产生了更高的电荷分离效率[21-22]。然而,迄今为止,包括P25 TiO2在内的光催化剂在自然界中直接被用于水净化的报道很少。这是因为在太阳光照射下,光催化剂表面产生的活性氧(ROS)不仅能够分解水中的污染物,还能破坏自然界中对环境有益的生物大分子[23-30]。此外,纳米催化剂还能够进入植物和动物的循环系统,造成额外的健康问题[31]。为了解决此类问题,一种方法是将常规光催化剂固定在具有微孔的多孔晶体结构中,如Beta沸石分子筛,从而实现对污染物分子选择性光降解。Beta沸石分子筛是一种具有稳定骨架结构和规则均匀的三维十二元环孔结构的高硅沸石[32-35],其独特的孔道结构对反应物具有一定的选择性作用,只允许小于孔径的有机污染物分子进入结构内部的光催化活性中心进行反应,而阻碍了大尺寸的生物分子接近光催化剂[36-38]。

本研究是将Pt QDs修饰的P25(Pt-modified P25)固定在Beta沸石晶体内部制备Pt-modified P25@Beta zeolite光催化剂。所制备的光催化剂具有环境友好的光催化性能,其对水溶液中苯胺类污染物可以实现高效选择性光降解。这种独特的高效选择性光催化的特性:一方面归因于Pt量子点表面等离子体共振可以有效地减小催化剂的带隙,抑制电子- 空穴对的复合,扩大太阳能光响应的光谱范围;另一方面是由于Pt-modified P25被沸石晶体包裹后形成的核壳结构具有选择性光降解苯胺污染物的能力,因为分子尺寸小于Beta沸石孔径的苯胺分子能够经自由扩散通过沸石鞘接触Pt-modified P25表面而产生光降解,与之相反,分子尺寸较大的叶绿素因无法通过沸石孔道从而避免受到损害。

1 实验 1.1 实验材料P25 TiO2、氯铂酸·六水合物(H2PtCl6 ·6H2O)、氢氧化钠(NaOH)、铝酸钠(NaAlO2)、四乙基氢氧化铵(C8H21NO, 25wt. %,TEAOH)、正硅酸乙酯(C8H20O4Si, TEOS)购自阿拉丁。乙醇(C2H5OH) 和氨水(NH4OH)购自天津富宇精细化工有限公司。硝酸铵(NH4NO3)购自天津福辰化学试剂有限公司。所有试剂均为分析纯,无需进一步纯化。

1.2 Pt-modified P25的制备将0.1 g P25 TiO2粉体分散在0.2 mL 4× 10-3 mol/L H2PtCl6溶液中,室温超声处理1 h, 100 ℃干燥24 h,400 ℃煅烧4 h,得到Pt-modified P25。

1.3 Pt-modified P25@SiO2的制备将15 mg Pt-modified P25分散到含有50 mL水和40 mL乙醇的混合溶液中,在室温下超声处理1 h,然后加入9.5 mmol TEOS,用NH4OH调节pH至10。50 ℃真空搅拌除去水和乙醇,100 ℃干燥12 h,得到掺杂Pt-modified P25@SiO2。

1.4 Pt-modified P25@Beta zeolite的制备将0.07 g NaAlO2和0.05 g NaOH溶解在3 mL水中,然后加入2.5 g TEAOH。搅拌30 min后,加入1.2 g Pt-modified P25@SiO2,持续搅拌,形成均匀悬浮液。然后将混合物转移到具有PTFE内衬的不锈钢高压釜中,140 ℃加热48 h,冷却至室温,离心,去离子水洗涤3次,100 ℃干燥,然后550 ℃煅烧4 h去除有机模板。将煅烧产物分散到50 mL 1 mol/L NH4NO3溶液中,80 ℃搅拌3 h,离心、洗涤、干燥,550 ℃煅烧4 h,此过程重复1次,得到Pt-modified P25@Beta zeolite。

1.5 表征样品的相结构是通过配有Cu-Kα辐射源(λ =0.154 2 nm)的X射线衍射仪(XRD, Smart Lab 3 kW)在40 kV和30 mA条件下表征。P25、Pt-modified P25和Pt-modified P25@Beta zeolite的微观形貌在3 kV的场发射透射电子显微镜(TEM, JSM-2100Plus, Japan Electronics Co., Ltd.)上观察。在室温下,装有积分球的UV-2600(岛津)PC光谱仪记录了固态紫外- 可见漫反射光谱。吸收光谱在紫外- 可见分光光度计(UV -2600, 岛津)上测量。光电化学测试在电化学工作站(CHI660E,上海辰华)上进行,在0.5 mol/L Na2SO4水溶液中采用三电极模式。

1.6 光催化实验光催化降解实验在带有磁力搅拌器的石英光反应器中进行。采用300 W带有紫外光截止滤光片(λ>420 nm)的氙灯(CEL-HXF300)模拟可见光照射,通过流动水冷却系统将反应温度控制

在30 ℃以下。具体实验过程为:将一定数量的光催化剂(30 mg P25,30 mg Pt-modified P25,或240 mg Pt-modified P25@Beta zeolite) 添加到含有0.64 g/L叶绿素和4.15×10-3 g/L苯胺的40 mL水溶液中。每次反应前,将反应液在室温黑暗条件下搅拌1 h,以达到吸附平衡,然后打开光源开始反应。每隔一定时间取3 mL反应液,离心得到上层清液。用紫外分光光度计(UV-2600) 分别在230和400 nm处测量苯胺和叶绿素的吸收峰强度。

2 结果与讨论 2.1 晶体结构、形貌与组成分析P25和Pt-modified P25的XRD谱如图 1所示。两种样品(101)、(004)、(200)、(105)、(211)、(204)和(215)晶面的衍射峰均位于25.3°、37.8°、48.0°、53.9°、55.1°、62.7°和75.1°处,可与TiO2的锐钛矿相(JCPDS No.84-1285)相对应,而位于27.4°、36.1°、41.2°和56.6°的特征峰对应于TiO2金红石相(JCPDS No.76-0649) 的(110)、(101)、(111)和(220)的4个晶面。并且, 样品中锐钛矿与金红石的比例可以通过计算相应的峰面积得到,约为3 ∶1。在Pt-modified P25的XRD谱图中,可以清楚地观察到在39.7°和46.3°处的典型峰,这归因于面心立方相Pt晶体(JCPDS 87-0640)的(111)和(200)晶面,表明Pt量子点成功修饰了P25。Pt-modified P25@Beta zeolite的XRD谱图显示,在7.8°、21.3°、22.4°、25.2°、26.9°和29.3°处出现(101)、(205)、(302)、(304)、(008)和(306) 晶面的典型峰,其对应于Beta沸石晶体结构(JCPDS No.47-0183)。而锐钛矿相和金红石相的特征峰的减弱是由于沸石晶体壳层对TiO2纳米结构包覆作用所造成的,上述结果证明,本实验所制备的纳米结构为Pt-modified P25@Beta zeolite。

|

图 1 P25、Pt-modified P25和Pt-modified P25@Beta zeolite的XRD谱图 Fig.1 XRD patterns of P25, Pt-modified P25 and Pt-modified P25@Beta zeolite |

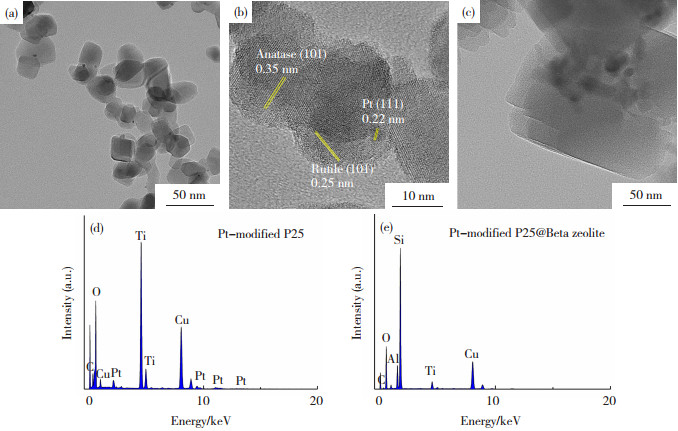

所制备的Pt-modified P25与Pt-modified P25@ Beta zeolite的透射电镜(TEM)、高分辨透射电镜(HRTEM)图像和能量色散X射线谱图(EDS)如图 2所示。

|

图 2 Pt-modified P25的TEM图像(a), HRTEM图像(b)及EDS谱图(d)和Pt-modified P25@Beta zeolite的TEM图像(c)及EDS谱图(e) Fig.2 TEM image, HRTEM image and EDS spectrum of (a, b, d) Pt-modified P25; TEM image and EDS spectrum of (c, e) Pt-modified P25@Beta zeolite |

从图 2(a)可以观察到,Pt-modified P25以纳米颗粒形式存在,尺寸约为25 nm, 同时清楚地发现Pt QDs较均匀沉积在P25 TiO2纳米颗粒表面。Pt-modified P25的HRTEM图像(图 2(b))显示,其存在3种不同类型的晶格条纹,其中,间距为0.35、0.25与0.22 nm的晶格条纹分别对应于锐钛矿的(101)晶面、金红石的(101)晶面与面心立方相Pt的(111)面。并且由图 2(d)可知Pt-modified P25中含有Ti、O、Pt等元素。上述结果证明Pt QDs成功负载在P25表面,与前述XRD谱图分析一致。从Pt-modified P25@Beta zeolite的TEM图像(图 2(c))中可以明显观察到,在沸石中,图像亮度呈黑暗色的Pt-modified P25颗粒的存在。Pt-modified P25@Beta zeolite的EDS显示,Pt-modified P25@Beta zeolite中含有Si、O、Al、Ti等元素,其中Pt元素由于本身含量少以及沸石鞘层的包裹而无法明显观察到其特征EDS谱峰的存在。上述结果表明,Pt-modified P25纳米颗粒成功被固定在Beta沸石晶体内部,形成了Pt-modified P25@Beta zeolite纳米复合结构。

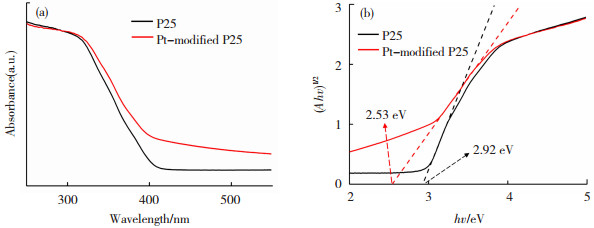

2.2 紫外- 可见漫反射光谱分析图 3(a)显示P25在可见光区约420 nm处有吸收边,Pt QDs改性后的P25在可见光区和紫外区的吸光度均有显著提高。这是由于Pt具有独特的光敏化和SPR效应,提高了太阳能的利用效率。所制备样品的带隙能(Eg)可通过以式(1)中hv与

| $ (a h v)^{1 / n}=A\left(h v-E_g\right) $ | (1) |

式中:a为光学吸收系数;hv为光子能量;A为常数。由于锐钛矿型TiO2是间接带隙半导体,n值为2.0[39]。如图 3(b)所示,P25和Pt-modified P25的Eg分别为2.92和2.53 eV。Pt-modified P25的带隙相较于P25明显减小,证明了Pt QDs的修饰增强了P25对太阳光能的吸收,从而使催化剂具有更高的氧化还原能力。

|

图 3 P25和Pt-modified P25的紫外- 可见漫反射光谱(a)和Tauc图(b) Fig.3 (a) UV-vis diffuse reflectance spectra and (b) corresponding Tauc plots of P25 and Pt-modified P25 |

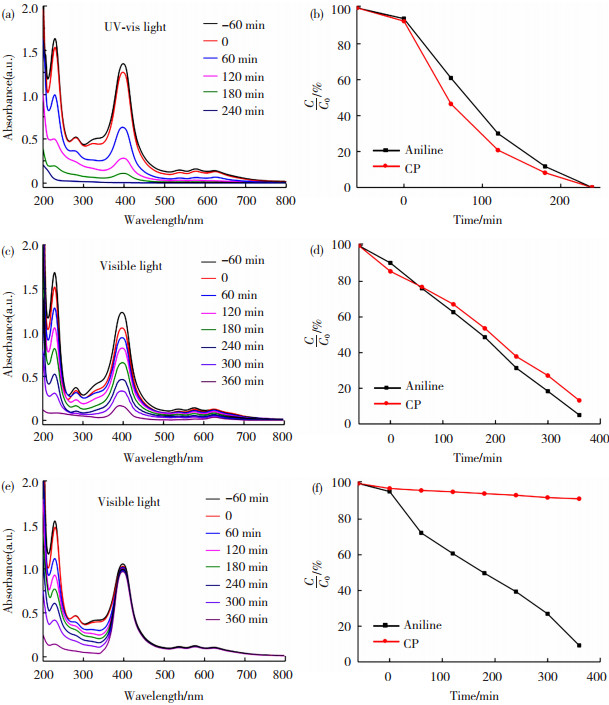

通过在紫外- 可见光照射下,对苯胺与叶绿素混合物水溶液进行光催化降解,研究了光催化剂的光催化性能。在所有的光降解反应中,苯胺作为有机污染物分子模型,而叶绿素作为自然界中的生物模型。所制备的纳米催化剂中Beta型沸石鞘孔尺寸约为0.71 nm,有利于小于沸石孔径的苯胺分子的扩散。从图 4(a)和(b)可以看出,在紫外光照射240 min后,P25表现出非常高的光催化性能,苯胺和叶绿素完全被降解。同时,Pt-modified P25在可见光照射360 min后,对苯胺和叶绿素同样具有很高的光降解率,分别为95.1%和86.9%(图 4(d))。这一结果表明,Pt QDs对P25的修饰可以增强P25在可见光条件下的光催化降解能力,这归因于Pt QDs的存在促进了电荷转移,抑制了电子- 空穴对的重组,并且Pt QDs表面等离子体共振效应可以有效减小P25的带隙,提高了P25的可见光响应。上述结果清楚地表明,与许多常规催化剂一样,P25和Pt-modified P25对苯胺污染物和有益的叶绿素分子的降解均是非选择性的。值得注意的是,在光催化降解实验中存在Pt-modified P25@Beta zeolite时,在可见光照射360 min后,苯胺污染物的光降解率高达90.8%,而叶绿素的光降解率仅为8.6%(图 4(f))。

|

图 4 光催化剂光催化降解苯胺和叶绿素水溶液时的紫外-可见光谱:(a) P25、(c)Pt-modified P25和(e) Pt-modified P25@Beta zeolite;对应的光降解速率图:(b) P25、(d) Pt-modified P25和(f) Pt-modified P25@Beta zeolite Fig.4 Photocatalytic performance of photocatalysts. UV-vis spectra of aqueous solutions of aniline and chlorophyll over catalysts: (a) P25, (c) Pt-modified P25 and (e) Pt-modified P25@Beta zeolite, and corresponding photodegradation rates of aqueous solutions of aniline and chlorophyll over catalysts: (b) P25, (d) Pt-modified P25 and (f) Pt-modified P25@Beta zeolite |

上述结果证明了所制备的Pt-modified P25@Beta zeolite在叶绿素存在的水介质中,对污染物的降解具有优异的形状选择性,这是由于Beta型沸石鞘具有孔径为0.71 nm的均匀微孔,只允许尺寸小于沸石微孔的苯胺污染物扩散,而阻止了叶绿素大分子通过沸石鞘到达光催化剂表面。此外,表 1展示了文献报道的光催化剂和本文所合成的光催化剂降解苯胺性能的对比结果,可以看出,在可见光照射下,本文所制备的Pt-modified P25与Pt-modified P25@Beta zeolite具有突出的光降解苯胺性能。

| 表 1 不同光催化剂的苯胺降解性能对比结果 Table 1 Comparison of aniline degradation performance of different photocatalysts |

图 5展示了可见光照射下Pt-modified P25@Beta zeolite光催化剂降解苯胺和叶绿素混合物水溶液的重复性实验。降解实验共重复5次,每次光照时间为360 min。Pt-modified P25@Beta zeolite对苯胺和叶绿素的光降解率每次稳定在91.2%和8.1%左右。上述数据表明,Pt-modified P25@Beta zeolite光催化剂在重复利用过程中能够保持良好的选择性,是一种循环稳定性好的光催化剂,具有较高的实用价值。

|

图 5 Pt-modified P25@Beta zeolite对苯胺和叶绿素降解的光催化循环性能测试 Fig.5 Photocatalytic activities of the Pt-modified P25@Beta zeolite in recycling tests in the degradation of aniline and chlorophyll for 360 min in each run |

为了进一步了解所制备光催化剂的光催化性能提升的原因,采用瞬态光电流响应和电化学阻抗谱(EIS)对光催化剂的光电化学性能进行了研究。瞬态光电流响应曲线是在有光/无光下间隔30 s重复4次获得的。如图 6(a)所示,Pt-modified P25的光电流密度明显高于P25,揭示了其具有更好的光响应和电荷转移特性,进一步证实了在P25上装饰Pt QDs可以有效提高二氧化钛的载流子分离效率。EIS测试结果如图 6(b)所示。Nyquist图半径越小,电子传递电阻越小,载流子分离越容易,光催化能力越强。在图 6(b)中可以明显观察到Pt-modified P25与P25相比具有更小的弧半径,这表明经过Pt QDs修饰后,光催化剂的电荷转移电阻和光生电子- 空穴对复合率降低。这一结果与上述瞬态光电流测试结果一致,进一步证实了在P25上装饰Pt QDs可以有效地促进载流子分离效率,增强催化剂的光催化活性。而Pt-modified P25@Beta zeolite没有表现出明显的光电流响应,并且具有最大的弧半径,这归因于Pt-modified P25固定在Beta沸石晶体内部后,其产生的光电流响应被沸石鞘层屏蔽。这些数据也与图 3和图 4中催化剂的光学和光降解性能的结果相吻合。

|

图 6 P25、Pt-modified P25和Pt-modified P25@Beta zeolite的瞬时光电流响应(a)和电化学阻抗谱(b) Fig.6 (a) Transient photocurrent responses and (b) corresponding electrochemical impedance plots of P25, Pt-modified P25 and Pt-modified P25@Beta zeolite |

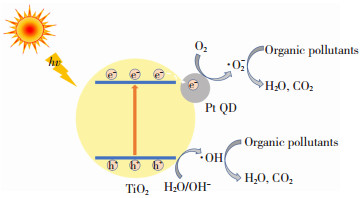

基于以上讨论,Pt-modified P25光催化降解苯胺等有机污染物的反应机理如图 7所示。在可见光照射下,P25的电子从价带被激发到导带,并在价带上留下空穴。由于铂的费米能级低于TiO2导带,在Pt/TiO2界面形成肖特基势垒,使得光生电子由P25的导带进一步转移到Pt QDs,阻止了光生电子与空穴的复合[43]。然后Pt QDs上的光生电子被水中吸附的氧分子(O2)捕获,形成超氧自由基(·O2-),同时,价带上的激发空穴会与催化剂表面的H2O反应生成羟基自由基(·OH)[22, 28]。最后,这些活性氧将水中的苯胺等有机污染物光降解转化为CO2和H2O等无害的小分子[44]。

|

图 7 Pt-modified P25的光降解示意图 Fig.7 Schematic photodegradation diagram of Pt-modified P25 |

本实验成功地制备了一种环境友好的光催化剂,即Pt-modified P25@Beta zeolite。Pt QDs的修饰不仅有效抑制了光生电子- 空穴对的重组,而且由于Pt的SPR效应,大大改善了TiO2的可见光响应。Pt-modified P25对污染物苯胺和有益的叶绿素均表现出很高的光催化性能,在可见光照射360 min后,光降解率分别达到95.1%和86.9%。

值得注意的是,Pt-modified P25@Beta zeolite对苯胺表现出突出的选择性光降解,光降解率可达90.8%,而有益的叶绿素的光降解率仅为8.6%。这是由于Pt-modified P25周围的沸石鞘微孔只允许分子尺寸较小的苯胺污染物通过,并在水中被充分光降解,而阻止了叶绿素大分子接近光催化剂表面。本研究为环境友好型光催化剂的制备提供了一种简单的方法。

| [1] |

CHEN Ying, LIU Yuan, LAN Tong, et al. Quantitative profiling of protein carbonylations in ferroptosis by an aniline-derived probe[J]. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 2018, 140(13): 4712-4720. DOI:10.1021/jacs.8b01462 |

| [2] |

LV Yanqing, YU Haitao, XU Pengcheng, et al. Metal organic framework of MOF-5 with hierarchical nanopores as micro-gravimetric sensing material for aniline detection[J]. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical, 2018, 256: 639-647. DOI:10.1016/j.snb.2017.09.195 |

| [3] |

LI Dan, LI Dawei, FOSSEY J S, et al. Portable surface-enhanced Raman scattering sensor for rapid detection of aniline and phenol derivatives by on-site electrostatic preconcentration[J]. Analytical Chemistry, 2010, 82(22): 9299-9305. DOI:10.1021/ac101812x |

| [4] |

LI Hongliang, KANAI M, KUNINOBU Y. Iridium/bipyridine-catalyzed ortho-selective C-H borylation of phenol and aniline derivatives[J]. Organic Letters, 2017, 19(21): 5944-5947. DOI:10.1021/acs.orglett.7b02936 |

| [5] |

JIAO Zinuo, ZHANG Yu, XU Wei, et al. Highly efficient multiple-anchored fluorescent probe for the detection of aniline vapor based on synergistic effect: Chemical reaction and PET[J]. ACS Sensors, 2017, 2(5): 687-694. DOI:10.1021/acssensors.7b00143 |

| [6] |

CHEN Ya, WANG Bin, WANG Xiaoqing, et al. A copper (Ⅱ)-paddlewheel metal-organic framework with exceptional hydrolytic stability and selective adsorption and detection ability of aniline in water[J]. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces, 2017, 9(32): 27027-27035. DOI:10.1021/acsami.7b07920 |

| [7] |

FENG Huijun, XU Ling, LIU Bing, et al. Europium metal-organic frameworks as recyclable and selective turn-off fluorescent sensors for aniline detection[J]. Dalton Transactions, 2016, 45(43): 17392-17400. DOI:10.1039/c6dt03358j |

| [8] |

TURESKY R J, MARCHAND L L. Metabolism and biomarkers of heterocyclic aromatic amines in molecular epidemiology studies: Lessons learned from aromatic amines[J]. Chemical Research in Toxicology, 2011, 24(8): 1169-1214. DOI:10.1021/tx200135s |

| [9] |

WANG Fengqin, DONG Caifu, WANG Chenmiao, et al. Fluorescence detection of aromatic amines and photocatalytic degradation of rhodamine B under UV light irradiation by luminescent metal-organic frameworks[J]. New Journal of Chemistry, 2015, 39(6): 4437-4444. DOI:10.1039/c4nj02356k |

| [10] |

GHOSH S, MALLOUM A, BORNMAN C, et al. Novel green adsorbents for removal of aniline from industrial effluents: A review[J]. Journal of Molecular Liquids, 2022, 345: 118167. DOI:10.1016/j.molliq.2021.118167 |

| [11] |

EBRAHIM E, AMIRI A, BAGHAYERI M, et al. Poly (indole-co-thiophene)@Fe3O4 as novel adsorbents for the extraction of aniline derivatives from water samples[J]. Microchemical Journal, 2017, 131: 174-181. DOI:10.1016/j.microc.2016.12.022 |

| [12] |

CUI Yue, LIU Xiangyang, CHUNG T S, et al. Removal of organic micro-pollutants (phenol, aniline and nitrobenzene) via forward osmosis (FO) process: Evaluation of FO as an alternative method to reverse osmosis (RO)[J]. Water Research, 2016, 91: 104-114. DOI:10.1016/j.watres.2016.01.001 |

| [13] |

YIN Yixin, ZHANG Qian, PENG Haojin. Retrospect and prospect of aerobic biodegradation of aniline: Overcome existing bottlenecks and follow future trends[J]. Journal of Environmental Management, 2023, 330: 117133. DOI:10.1016/j.jenvman.2022.117133 |

| [14] |

ZHANG Chengji, CHEN Hong, XUE Gang, et al. A critical review of the aniline transformation fate in azo dye wastewater treatment[J]. Journal of Cleaner Production, 2021, 321: 128971. DOI:10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.128971 |

| [15] |

ORGE C A, FARIA J L, PEREIRA M F R. Photocatalytic ozonation of aniline with TiO2-carbon composite materials[J]. Journal of Environmental Management, 2017, 195: 208-215. DOI:10.1016/j.jenvman.2016.07.091 |

| [16] |

LOU Lihua, KENDALL R J, RAMKUMAR S. Comparison of hydrophilic PVA/TiO2 and hydrophobic PVDF/TiO2 microfiber webs on the dye pollutant photo-catalyzation[J]. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering, 2020, 8(5): 103914. DOI:10.1016/j.jece.2020.103914 |

| [17] |

ALI I, KIM S R, KIM S P, et al. Anodization of bismuth doped TiO2 nanotubes composite for photocatalytic degradation of phenol in visible light[J]. Catalysis Today, 2017, 282: 31-37. DOI:10.1016/j.cattod.2016.03.029 |

| [18] |

MENG Aiyun, ZHANG Liuyang, CHENG Bei, et al. Dual cocatalysts in TiO2 photocatalysis[J]. Advanced Materials, 2019, 31(30): 1807660. DOI:10.1002/adma.201807660 |

| [19] |

CHEN Qifeng, WANG Hui, WANG Cuicui, et al. Activation of molecular oxygen in selectively photocatalytic organic conversion upon defective TiO2 nanosheets with boosted separation of charge carriers[J]. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental, 2020, 262: 118258. DOI:10.1016/j.apcatb.2019.118258 |

| [20] |

GUO Qing, ZHOU Chuanyao, MA Z B, et al. Fundamentals of TiO2 photocatalysis: Concepts, mechanisms, and challenges[J]. Advanced Materials, 2019, 31(50): 1901997. DOI:10.1002/adma.201901997 |

| [21] |

LI Wei, LIU Chang, ZHOU Yaxin, et al. Enhanced photocatalytic activity in anatase/TiO2(B) core-shell nanofiber[J]. Journal of Physical Chemistry C, 2008, 112(51): 20539-20545. DOI:10.1021/jp808183q |

| [22] |

DING Z, LU G Q, GREENFIELD P F. Role of the crystallite phase of TiO2 in heterogeneous photocatalysis for phenol oxidation in water[J]. Journal of Physical Chemistry B, 2000, 104(19): 4815-4820. DOI:10.1021/jp993819b |

| [23] |

CHEN Qifeng, WANG Keyan, GAO Guoming, et al. Singlet oxygen generation boosted by Ag-Pt nanoalloy combined with disordered surface layer over TiO2 nanosheet for improving the photocatalytic activity[J]. Applied Surface Science, 2021, 538: 147944. DOI:10.1016/j.apsusc.2020.147944 |

| [24] |

LIVRAGHI S, CORAZZARI I, PAGANINI M C, et al. Decreasing the oxidative potential of TiO2 nanoparticles through modification of the surface with carbon: A new strategy for the production of safe UV filters[J]. Chemical Communications, 2010, 46(44): 8478-8480. DOI:10.1039/c0cc02537b |

| [25] |

XIA Bin, CHEN Bijuan, SUN Xuemei, et al. Interaction of TiO2 nanoparticles with the marine microalga nitzschia closterium: Growth inhibition, oxidative stress and internalization[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2015, 508: 525-533. DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2014.11.066 |

| [26] |

MORLANDO A, SENCADAS V, CARDILLO D, et al. Suppression of the photocatalytic activity of TiO2 nanoparticles encapsulated by chitosan through a spray-drying method with potential for use in sunblocking applications[J]. Powder Technology, 2018, 329: 252-259. DOI:10.1016/j.powtec.2018.01.057 |

| [27] |

ZARA D L, BAILER M R, HAGEDOOM P, et al. Sub-nanoscale surface engineering of TiO2 nanoparticles by molecular layer deposition of poly(ethylene terephthalate) for suppressing photoactivity and enhancing dispersibility[J]. ACS Applied Nano Materials, 2020, 3(7): 6737-6748. DOI:10.1021/acsanm.0c01158 |

| [28] |

CHAKHTOUNA H, BENZEID H, ZARI N, et al. Recent progress on Ag/TiO2 photocatalysts: Photocatalytic and bactericidal behaviors[J]. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 2021, 28(33): 44638-44666. DOI:10.1007/s11356-021-14996-y |

| [29] |

LAU Z L, LOW S S, EZEIGWE E R, et al. A review on the diverse interactions between microalgae and nanomaterials: Growth variation, photosynthetic performance and toxicity[J]. Bioresource Technology, 2022, 35: 127048. DOI:10.1016/j.biortech.2022.127048 |

| [30] |

SADIQ I M, DALAI S, CHANDRASEKARAN N, et al. Ecotoxicity study of titania (TiO2) NPs on two microalgae species: Scenedesmus sp. and chlorella sp.[J]. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 2011, 74(5): 1180-1187. DOI:10.1016/j.ecoenv.2011.03.006 |

| [31] |

LI Fengmin, LIANG Zhi, ZHANG Xiang, et al. Toxicity of nano-TiO2 on algae and the site of reactive oxygen species production[J]. Aquatic Toxicology, 2015, 158: 1-13. DOI:10.1016/j.aquatox.2014.10.014 |

| [32] |

LU Tingting, YAN Wenfu, XU Ruren. Chiral zeolite beta: Structure, synthesis, and application[J]. Inorganic Chemistry Frontiers, 2019, 6(8): 1938-1951. DOI:10.1039/c9qi00574a |

| [33] |

YOU H S, JIN Hailian, MO Y H, et al. CO2 adsorption behavior of microwave synthesized zeolite beta[J]. Materials Letters, 2013, 108: 106-109. DOI:10.1016/j.matlet.2013.06.088 |

| [34] |

SHEN Zheng, CHEN Wenbo, ZHANG Wei, et al. Efficient catalytic conversion of glucose into lactic acid over Y-β and Yb-β zeolites[J]. ACS Omega, 2022, 7(29): 25200-25209. DOI:10.1021/acsomega.2c02051 |

| [35] |

ZHU Zhiguo, XU Hao, JIANG Jinggang, et al. Hydrophobic nanosized all-silica Beta zeolite: Efficient synthesis and adsorption application[J]. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces, 2017, 9(32): 27273-27283. DOI:10.1021/acsami.7b06173 |

| [36] |

MARTHALA V R R, FRIEDRICH M, ZHOU Z, et al. Zeolite-coated porous arrays: A novel strategy for enzyme encapsulation[J]. Advanced Functional Materials, 2015, 25(12): 1832-1836. DOI:10.1002/adfm.201404335 |

| [37] |

TUEL A, FARRUSSENG D. Hollow zeolite single crystals: Synthesis routes and functionalization methods[J]. Small Methods, 2018, 2(12): 1800197. DOI:10.1002/smtd.201800197 |

| [38] |

HE Zhen, WU Juan, GAO Bingying, et al. Hydrothermal synthesis and characterization of aluminum-free Mn-β zeolite: A catalyst for phenol hydroxylation[J]. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces, 2015, 7(4): 2424-2432. DOI:10.1021/am507134g |

| [39] |

ZHANG Xinnan, GE Mingzheng, DONG Jianing, et al. Polydopamine-inspired design and synthesis of visible-light-driven Ag NPs@C@elongated TiO2 NTs core?shell nanocomposites for sustainable hydrogen generation[J]. ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering, 2019, 7(1): 558-568. DOI:10.1021/acssuschemeng.8b04088 |

| [40] |

KIANI M T, RAMAZANI A, FARDOOD S T. Green synthesis and characterization of Ni0.25Zn0.75Fe2O4 magnetic nanoparticles and study of their photocatalytic activity in the degradation of aniline[J]. Applied Organometallic Chemistry, 2023, 37(4): e7053. DOI:10.1002/aoc.7053 |

| [41] |

DING Xiaohui, LI Chunhu, WANG Liang, et al. Fabrication of hierarchical g-C3N4/MXene-AgNPs nanocomposites with enhanced photocatalytic performances[J]. Materials Letters, 2019, 247: 174-177. DOI:10.1016/j.matlet.2019.02.125 |

| [42] |

SBOUI M, LACHHEB H, BOUATTOUR S, et al. TiO2/Ag2O immobilized on cellulose paper: A new floating system for enhanced photocatalytic and antibacterial activities[J]. Environmental Research, 2021, 198: 111257. DOI:10.1016/j.envres.2021.111257 |

| [43] |

PEPIN P A, LEE J D, MURRAY C B, et al. Thermal and photocatalytic reactions of methanol and acetaldehyde on Pt-modified brookite TiO2 nanorods[J]. ACS Catalysis, 2018, 8(12): 11834-11846. DOI:10.1021/acscatal.8b03081 |

| [44] |

LI Wei, CHEN Cheng, ZHU Junyi, et al. Efficient removal of aniline by micro-scale zinc-copper (mZn/Cu) bimetallic particles in acidic solution: An oxidation degradation mechanism via radicals[J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2019, 366: 482-491. DOI:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2018.12.027 |

2024, Vol. 32

2024, Vol. 32