2. Department of Electrical and Electronics Engineering, University College of Engineering Panruti, Panruti 607106, India

Electric Vehicles (EVs) focus on advancing battery technologies for extended range and rapid charging capabilities. Despite progress in enhancing battery energy density and reducing costs, challenges persist in developing cost-effective batteries with higher energy densities, faster charging rates, and longer life cycles. Additionally, research on sustainable materials and recycling processes is imperative to address environmental concerns related to battery production and disposal. Optimizing EV charging infrastructure and grid integration are essential for widespread EV adoption, necessitating the development of smart charging algorithms and demanding response strategies to manage charging demand, mitigating grid impacts, and optimizing energy usage. Moreover, exploring interoperability standards, communication protocols and grid-edge technologies, is vital for the seamless integration of EV charging with renewable energy sources and grid management systems.

Furthermore, addressing consumer acceptance and adoption barriers for EVs, including concerns about driving range, charging infrastructure availability, upfront costs, and perceived reliability, is crucial. Understanding consumer preferences, behaviors, and decision-making processes can inform the design of effective incentive programs, marketing strategies and policy interventions, to accelerate EV adoption and market penetration. Additionally, exploring potential synergies between EVs and emerging technologies, such as autonomous driving, V2G (Vehicle-to-Grid) integration and shared mobility services, is essential. Investigating the interactions and impacts of these technologies on transportation systems, energy markets and urban infrastructure can provide valuable insights into the future evolution of mobility and energy systems. In conclusion, addressing these categories can advance the adoption, deployment, and integration of EVs within transportation systems and energy networks, ultimately supporting the transition to a more sustainable and decarbonized transportation sector.

Enhancing the quality of the air, energy security, atmospheric conditions free from pollution, and economic opportunity, the Indian automobile industry is rapidly turning into a promising channel, which is electric vehicles. A progressing country such as India has a wide look into the reduction of dependency on imported energies, reducing the emissions of greenhouse gases, and advancement in transportation to reduce the adverse effects of global warming[1].

The electric vehicle market has experienced remarkable growth, with major automotive manufacturers making substantial investments in research and development to introduce innovative and competitive electric models. At the heart of electric vehicles lies electric powertrains with electric motors powered by rechargeable batteries, replacing traditional internal combustion engines. This transition not only reduces dependence on fossil fuels but also significantly lowers greenhouse gas emissions, aiding in climate change mitigation. Recent advancements in battery technology, particularly in energy density and cost reduction, have played a crucial role in improving the range and affordability of electric vehicles. In India, there has been a notable surge in the adoption of electric vehicles in recent years[2]. Kailashkumar et al.[2] examine the current landscape of electric vehicles in the Indian market, encompassing government initiatives, infrastructure expansion, challenges, and future prospects. The analysis underscores the driving factors behind EV adoption, the status of charging infrastructure, the policy framework, and the environmental and economic impacts of electric mobility.

Emission of carbon dioxide emission can be minimized by taking proper action over the catastrophic climate change which is the main issue that gives maximum threats to all the living organisms in the world. While generating power, more fossil fuels have been used, and many efforts have been taken to minimize the usage of those fuels as well as energy consumption. An alternative way to reduce the emission of carbon dioxide is shifting towards electric vehicles. Even though the use of EVs has started, many people use vehicles that are purely dependent on fossil fuels. In contrast to traditional fossil fuel-driven vehicles, EVs raise important considerations related to charging, life cycle assessment, and driving range. A vehicle with an IC (Internal Combustion) engine emits around 120 g/km of carbon dioxide based on tank-to-wheel measurements, but this figure increases to 180 g/km from a life cycle assessment perspective. On the contrary, EVs produce zero emissions of carbon dioxide based on tank-to-wheel measurements. Therefore, the carbon dioxide emissions from EVs heavily depend on the sources of power used during the manufacturing and driving of the vehicle. Because of huge emissions from the ICEV (Internal Combustion Engine Vehicle) in the transport sector and other equipment manufacturers, the growth and need for EVs have been developed in the last few decades. The expansion of EVs in India hinges on the presence of charging infrastructure facilities, government policy support, incentives for purchasing, parking facilities, and with latest upgraded technologies. Currently, the production rate and market presence of EVs in India remain relatively low and negligible. However, there is a growing interest in electric bicycles, electric bikes/scooters, e-rickshaws, and e-cars in the country.

Electric vehicles can be widely adopted to standardize the grid, especially in the context of fluctuating renewable energy generation[3]. Because of low power consumption, electric vehicles do not have a greater impact on electricity market transactions[4]. Many researchers have extensively studied the evaluation of current smart policies within dynamic scenarios, which are considered exogenous factors. In order to fully exploit the maximum potential, the effective implementation of flexible load management and smart charging strategies are crucial[5-9]. The EV users are very aware of charging operations by aggregating the energy necessity and timing with their battery level supports[10]. The pricing signals have been provided to the EV users to framework the centralization and decentralization overlaps[11].

In early 2016, dynamic travel scheduling and charging profiles were successfully tested and simulated by Brady et al.[12]. They stated that overall accuracy can be enhanced by increasing the accuracy and distribution of parking times. Subsequently, Morrissey et al.[13] conducted a study and unveiled that electric vehicle users display a preference for charging their vehicles at home, particularly during the evening peak electricity demand. Foley et al.[14] investigated the effects of EV charging under various scenarios, encompassing both off-peak and peak timings. Their results showed that charging during peak times leads to a more significant impact compared to off-peak charging. By exploring the primary obstacles to EVs, the objective of Steinhilber et al.'s[15] work is to pinpoint vital tools and strategies for implementing new technology and fostering innovation in the EV industry. Using trip segment partitioning, the distance a vehicle can travel has been assessed through driving pattern recognition techniques under various driving conditions[16].

The proper investigation was done over the topographies build-up of the vehicle model and with different driving conditions by Hayes et al.[17]. In Switzerland, the EV charging impact on the distribution channel in specified locations and higher penetration level was found, resulting in an increased risk of overloads because of dynamic traffic[18]. Subsequently, various parameters associated with EVs were measured and compared against range types. Several studies[19-23] also analysed the impact of charging methodology on the national grid, considering storage utilization, and examined the non-linear performance by estimating the torque of permanent magnet synchronous motors for hybrid electric vehicles. The highest torque that can be transmitted and stability are enhanced by augmenting the antiskid efficiency of the torque control system[24-25]. In 2013, Lu et al.[26] carried out an extensive review of electric vehicles, focusing specifically on critical aspects of Li-ion battery management, notably addressing challenges related to voltage, battery state estimation, equalization, and fault analysis. These can be more useful for researchers to design an efficient battery management system. Modelling approaches for electric vehicles, energy management, and optimal strategies were studied and reviewed[27-30].

Different evaluation methods and indicators are proposed to uncover the vulnerability of the distribution network and provide improvement measures, have also categorized different factors both internal and external factors influencing the vulnerability of distributed networks, Yang et al.[31] suggested the EENS (Equivalent Energy Not Served) can be useful in distribution networks for analysing vulnerability and remaining life of lithium-ion batteries. By incorporating the evaluation index and evaluation method, DTR (Dynamic Thermal Rating) improves EENS, which could enable real-time monitoring and assessment of potential failure risks and vulnerable components. The network topology optimization technique optimizes busbar switching and lines for reducing congestion in the network and enhancing the flexibility of the network. To improve the ratings of the overhead lines, DTR is used, Lai et al.[32] also determined the prevailing security standards of large-scale integrated wind network, implemented a reliability test in modified IEEE 24bus, and explained reduced system dispatch, wind curtailment costs and load curtailment in isolation.

Alanazi et al.[33] explored the potential of EVs and their integration into smart cities, highlighting both their benefits and the obstacles to widespread adoption. Challenges such as range anxiety, inadequate infrastructure, and high battery costs are identified. However, Alanazi et al.[33] suggested that incorporating EVs into smart city initiatives can lead to sustainable and efficient urban environments characterized by lower operating expenses, decreased greenhouse gas emissions and enhanced air quality. Overcoming these challenges is feasible through the development of robust charging infrastructure, deployment of smart grid technologies, and leveraging data analytics. By encouraging EV usage within smart cities, we can cultivate more sustainable and liveable urban areas that prioritize the health and well-being of residents while also reducing our carbon footprint.

The Reva electric car emerged as the first electric vehicle of an Indian company during the early 2000s, pioneering the production of technologically advanced vehicles offered at affordable prices with a wide array of features. Mahindra Electric Mobility Ltd is the foremost producer of BEV in India, and others like Toyota Kirloskar Motor Pvt Limited, Honda Motors Co. Ltd and Volvo Car Corporation are the leading major manufacturers of Hybrid Electric Vehicle (HEV)[34]. In 2014, India's overall emissions of greenhouse gases reached 3202 million metric tons of carbon dioxide, contributing to more than 6.5% of worldwide emissions of greenhouse gas. Additionally, 68% of these emissions were attributed to the energy sectors. Agriculture, forestry improvements, and manufacturing activities also had notable impacts on greenhouse gas emissions in the country[35]. To enhance the utilization of electric vehicles, integrating them with the grid during charging and discharging can be advantageous. This integration can be achieved through various modes, including V2G, G2V (Grid to Vehicle), and V2B (Vehicle to Building). Generally, EVs are in charging mode while connected as G2V, EVs discharge energy to the grid while connected as V2G, utilizing the capability of bi-directional energy flow control in regular intervals between vehicles and grids, making it function as a portable battery storage system. In the case of V2B, the energy can be securely transferred from the vehicle to the building while it remains connected to the charging port. Su et al.[36] highlighted the relative balance between the information system, physical system, and social system, utilizing a cloud edge end architecture to construct a distributed cyber physical system. A three-stage optical scheduling approach was introduced for distributed cyber physical systems within hybrid AC/DC distribution networks, which also incorporated electric vehicles. To address communication delays and disturbances such as noise, a Non-ideal Communication Alternating Direction Multiplier Method(NC-ADMM) algorithm was developed. This algorithm significantly improved the convergence speed of the system. And lastly, the three-stage optimal scheduling framework effectively achieves optimized operation of EVs and Renewable Distributed Generators (RDGs) over different time intervals. This enhances RDG absorption capacity and reduces the impact of uncertainties[36].Authors in Ref.[37] classified various community microgrids based on distinct load characteristics to create an advanced hybrid distribution system. A three-stage utilization framework has been introduced, enabling the operation of dispatchable resources across different time scales for improved performance. Additionally, a cloud-edge collaborative architecture is proposed to support hierarchical distributed management between the Distribution System Operator(DSO) and community microgrids.

Su et al.[38] focused on the uncertainty that occurs in the network and established an AC/DC hybrid active distribution systems model, considering the dynamic thermal rating, distribution network reconfiguration and SOP (Standard Operating Procedure). Optimal operation was realized through day ahead and intraday framework-based scheduling dispatches. Synergistic optimization improves the absorption capacity and reduces the line loss, this dispatching can adapt to fluctuations in DGs (Distributed Generations) and loads. Dynamic thermal rating is employed to improve the reliability of transmission lines, primarily through two models: the Arrhenius model and the Weibull model. While operating at higher temperatures, loading effect of the dynamic thermal rating is also considered in the Arrhenius model. On the other hand, Weibull model deals with transmission lines by considering end-of-life failure effects and it was implemented based on IEEE 738 standards. It provides more accurate and reliable modelling of the transmission lines during failure events, by including the correlation factor of the weather data, which is more important for a realistic power system[39].

Various challenges and barriers to EV evolution in developing countries, such as India, have been overviewed here. The main focus is on the actual adaptation of EVs and not on the intervention because of the wide growth of EV markets by considering the difference between the actual behaviour and intended actions. This study focuses on identifying the various barriers and challenges associated with the usage of battery-operated vehicles. Additionally, it aims to raise awareness about the added advantages of battery-operated vehicles compared to conventional fossil-fuelled vehicles in developing countries like India. The research also examines the initiatives and actions implemented to encourage hybrid vehicles in such regions. The potential research gaps in the field of EVs are as follows.

1) Battery technology improvement is a crucial area that needs to be focused on developing cost-effective batteries with higher energy densities, faster-charging rates, and longer cycle lives.

2) Sustainable materials and recycling processes play a vital role in the development and lifecycle management of EVs. Key factors include the recycling of battery materials, vehicle components (such as interiors, panels, and chassis), supply chain transparency, and the implementation of regulatory frameworks and policies like Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) and End-of-Life Vehicle (ELV) regulations.

3) Optimization of charging infrastructure and grid integration for electric vehicles lies in the development of innovative algorithms and technologies to address the increasing demand for EV charging while minimizing grid congestion, maximizing the utilization of renewable energy sources, and ensuring overall grid stability and reliability. This entails exploring novel approaches for efficient charging station placement, demand response strategies, and communication protocols to support the seamless integration of EVs into the grid.

4) Consumer acceptance and adoption barriers for electric vehicles involve identifying and addressing specific concerns such as driving range anxiety, limited charging infrastructure, high upfront costs, and perceived reliability issues. Further research is needed to understand consumer preferences, behaviours, and decision-making processes to inform the design of effective incentive programs, marketing strategies, and policy interventions aimed at accelerating EV adoption and market penetration.

5) Synergies with emerging technologies involve exploring the interactions and impacts of EVs with autonomous driving, V2G integration, and shared mobility services. Further research is needed to understand how these technologies can be integrated effectively to optimize transportation systems, energy markets, and urban infrastructure, providing valuable insights into the future evolution of mobility and energy systems.

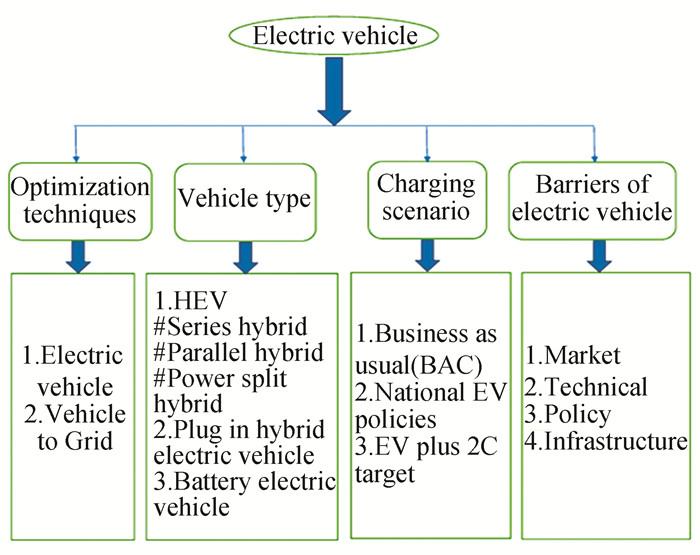

1 MethodologyIn the current scenario, there are several types of EVs available that are studied for understanding the various barriers in it and discussed the different types of optimization techniques that can be implemented. Similarly, studies about the EVs and their overviews are represented below in Fig. 1.

|

Fig.1 Electric vehicles overview |

In this paper, we have made the content into several sections to provide a clearer understanding of the methodology, configurations, and key insights, including the nature of charging, different categories of barriers, challenges, and the various techniques used in V2G and G2V systems. The paper concludes with a summary of key findings.

1.1 OverviewThe main phenomenon of implementing EVs is to minimize the use of an IC engine with motors, especially with electric motors, which are generally operated using energy storage devices or batteries with the help of power electronics equipment. Generally, we know that electric motors are very efficient as they use 90% to 95% of the total input energy (electrical energy). The most important components that seem to be the backbone for the operation of EVs are the battery, charging terminal, a rectifier utilized to convert AC (Alternating Current) to pulsating DC (Direct Current), a chopper utilized for transforming constant DC into adjustable DC, an inverter that deals with the conversion of DC into AC, braking systems, and driving systems.

As the EVs are charged using the eco-friendly mode which has lower power emission energy storage devices called batteries, charged directly from the electric grid, electric vehicles receive power with the assistance of a rectifier and other power electronics components. Generally, batteries are used to supply power to the motor, enabling it to operate or rotate and fulfil its essential functions.Because of the lightweight feature and low-cost maintenance, Li-ion batteries are widely used for their higher efficiency topology, even though their manufacturing cost is high when compared to other types of batteries. Under typical conditions, lithium-ion batteries have a lifespan of 8 to 12 years, which remains consistent regardless of climate and other environmental factors.

EVs are linked to the charging point, either the grid or charger which drags power from external power sources. The charger is responsible for recharging the vehicle's battery. Typically, an AC power source is connected to the charger, which converts the AC to DC. The charger then manages the battery changing process, regulating current, voltage, state of charge, and temperature throughout the cycle. The high-voltage DC is subsequently reduced using a chopper (DC-DC Converter) before being delivered to the vehicles. The speed of the propulsion motor can be controlled by the power electronics converters, and that power flow can be employed to control the torque.

Regenerative braking serves the dual purpose of enhancing energy efficiency and maintaining/improving the vehicle's strength. This process involves converting the kinetic energy (mechanical energy from the motor) into electric energy, which is then stored back into the battery. This type of braking is widely used in all kinds of EVs, such as hybrid EVs and BEVs, as it improves the coverage of EVs to cover more distance. Because of this, 15% of the energy is used for acceleration. The motion was generated and transferred that mechanical energy into the traction wheels aided by driving systems. EVs have various internal configurations, eliminating the need for conventional transmissions. This design choice results in fewer components, contributing to the simplicity of EVs when compared to internal combustion or gasoline-powered vehicles. However, this advantage comes with a trade-off in terms of acceleration, as EVs might not achieve the same speed as gasoline vehicles.

1.2 Categories of Electric VehiclesMost countries developed their design of EVs, but the market is broader in China, Japan, the United Kingdom, Germany, and the USA. Those vehicles are categorized into three groups, normally Hybrid Electric Vehicles (HEV), Plug in Hybrid Electric Vehicle (PHEV), and Battery Electric Vehicles (BEV).

1.2.1 Hybrid electric vehicleGenerally, this category of hybrid vehicle consists of both electric motors and internal combustion engines. The vehicle's battery charges through engine operation and harnessing energy generated during deceleration and braking. In current situation, hybrid vehicles are equipped with engines, motor, batteries and power converters.This type of vehicle modelling was engaged throughout the world because of the advantage of charging infrastructure independence, and the lower fuel consumption because of the electrification of power trains.

HEVs are classified based on their topologies, such as hybrid, power-split hybrid, and parallel hybrid. In a hybrid vehicle of the series configuration, the electric motor is instrumental in supplying power to the wheels. The motor draws power either from the battery or from the generator. The batteries in this type of vehicle are charged using IC engines, allowing them to provide power for driving the electric motor and receiving power from the engine/generator as well as regenerative braking. This process energizes the entire battery unit[40]. This type of vehicle has a bigger size of the battery pack and a small IC engine with a large electric motor, which is mostly assisted using ultra-capacitors, which can improve the effectiveness of the battery as well as the vehicle. Series hybrid drive trains have the advantage of utilizing regenerative energy recuperation while braking and delivering peak energy during acceleration. The electric motor's optimal torque-speed performance traits eliminate the need for a multi-gear transmission, which is a significant advantage. Moreover, the mechanical decoupling between the IC engine propels the IC engine utilizing the drive wheels to operate in its narrow optimal region, further optimizing performance.

However, there are some disadvantages to employing a drive train in a series hybrid. Firstly, overall efficiency can be reduced due to the energy being converted twice, from mechanical energy to electrical energy and then back to mechanical energy. Secondly, these vehicles require a large traction motor and two electric machines as they are the sole torque sources for the driven wheel. Consequently, series hybrid vehicles are commonly used in applications with ample space to accommodate their large engine/generator systems, such as military vehicles, commercial vehicles, and buses[41].

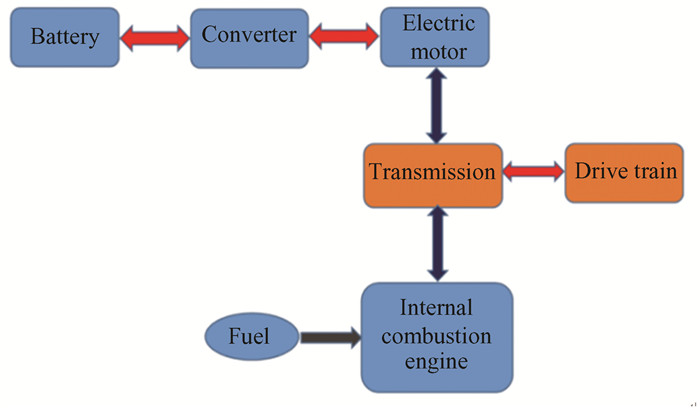

1.2.2 Parallel hybrid electric vehicleIn a parallel hybrid drive train, the engine is directly connected to the wheels, resulting in reduced energy losses and limited flexibility in positioning power train components, unlike the series hybrid drive train. The vehicle's wheels can receive power from the engine, the motor, or a hybrid of both. As a result, in a parallel hybrid, the vehicle can be driven exclusively by the engine, solely by the motor, or by a combination of both. In these systems, smaller battery packs are typically utilized, relying on regenerative braking to recharge. A power-split hybrid system comprises a motor, generator, and engine interconnected to a transmission with a planetary gearbox. This configuration can be adapted to both parallel and series setups within a single frame. The vehicle can be powered solely by the battery or the engine, or by a joint operation of both, while the battery can be simultaneously charged through the engine. The torque and speed of each component can be adjusted to determine the power delivered to the wheels, thereby optimizing engine efficiency. Fig. 2 demonstrates the power flow of a parallel hybrid drive train.

|

Fig.2 Parallel hybrid electric vehicle |

A PHEV combines both an internal combustion engine and an electric motor, utilizing both gasoline and a rechargeable battery that can be charged by electricity. This integration offers several advantages, such as a significant reduction in petroleum consumption by about 30%-60% compared to conventional vehicles. Thus, reducing petroleum usage is key to lowering dependence on oil, as a large share of electricity is sourced from domestic energy production. Moreover, PHEVs contribute to lower greenhouse gas emissions in contrast to traditional vehicles, although the actual emission levels vary based on the source of electricity production. For instance, electricity generated from nuclear and hydropower plants is much cleaner than that from coal-fired power plants.

Recharging a PHEV can be a time-consuming process. Charging through a 120 V household outlet may require several hours, but opting for a 240 V home or public charger can significantly reduce the charging time to a range of 1 to 4 h. For quicker charging, fast charging methods can easily restore up to 80% of the battery capacity in as short as 30 min. It is essential to understand when PHEVs do not necessarily require frequent charging, their maximum range and fuel economy cannot be achieved. To estimate the fuel economy of PHEVs, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) offers evaluations for different operating modes-gasoline-only, electric-only, or combined gas and electric operation-applicable to both city and highway driving scenarios. The advantage of PHEVs lies in their versatility, allowing them to operate on electricity, gasoline, or a combination of both, depending on the driving conditions and charging availability.

In 2015, China launched the world's largest charging station powered by solar energy that can charge up to 80 electric vehicles per day. In addition to that, a pilot project was initiated in Shanghai to experiment with the integration of sustainable power sources into the electric grid. In 2015, Japan installed more electric charge points, fuelled by solar photovoltaic systems, than the number of petrol stations. As of 2018, the top few countries leading in electric vehicle sales are China, several European countries, the USA, and Norway[42].

Manufacturers are announcing several innovative EV models that are expected to be available at lower prices in the coming years. Plug-in electric vehicles are becoming a promising gateway for reducing CO2 emissions and decreasing dependency on fossil fuels. Various studies have been conducted globally on hybrid electric vehicles. Researchers have explored different approaches, such as agent-based, micro-simulation, and model-based non-linear observers, to estimate torque and energy management for hybrid electric vehicles.

In China, Wu et al.[43] focused on developing a feed-forward model to analyse the optimal energy management strategy for a heavy-duty parallel hybrid electric truck. The results of this investigation revealed that the dynamic programming algorithm played a significant role in enhancing the vehicle's mileage. Wu et al.[43] also conducted convex programming based on an optimal control scheme, which demonstrated remarkable accuracy and was approximately 200 times faster than dynamic programming. Furthermore, this approach exhibited higher cost-effectiveness when compared to the heuristic PHEV scenario. By analysing PHEVs worldwide using random adaptive programming to optimize electric power allocation among utility grids, home power demand, and PHEV batteries. It was found that flexible capacity choice and improved fuel cell life span can result in better performance and lower life cycle costs for PHEVs.

Bashash et al.[44] estimated a multi-objective function by utilizing a genetic algorithm for optimizing the charge pattern of PHEVs, considering both energy and battery health costs. The study by Hadley et al.[45] explored the impact of PHEV penetration into the power grid on generation and emissions.Kelly et al.[46] investigated PHEV load profile charging, gasoline consumption, and charging characteristics using data from 17000 electric vehicles. Table 1 presents additional research on PHEVs conducted worldwide.

| Table 1 Plug-in hybrid EVs: A comprehensive overview |

In 2009, Marano et al.[56] conducted a study estimating the lifespan of lithium batteries in PHEV applications under driving conditions and real driving cycles. They created a battery life prediction model using accumulated charge to simulate aging. Campbell et al.[57] presented the optimization design of a Li-ion (lithium) cell battery pack for PHEVs and BEVs. When PHEVs are large enough, they can serve as backup storage for excess renewable energy[58]. Numerous researchers have explored the barriers, trends, and financial feasibility of electric vehicles of plug-in type in the USA, along with their impact on distribution networks[59-64].

1.2.3 Battery electric vehicleBEVs are fully electric vehicles that use high-capacity rechargeable battery packs to operate the internal electronics and also electric motor. They can reduce carbon dioxide emissions from light-duty vehicles and reduce dependence on fossil-fuelled vehicles. BEVs secured the largest market share in India, representing over 70% of the trade in 2017[65]. This trend is projected to maintain its growth trajectory in the upcoming years. Historically, BEVs were the preferred choice over PHEVs in various countries until 2014.

Nevertheless, the popularity of PHEVs has experienced a note-worthy surge in recent years, resulting in nearly equal sales with BEVs. In India, batteries are classified into three types: nickel-metal hydride batteries, lithium-ion, and lead-acid batteries. Various literature compares strategies for estimating the SOH (State of Health) and SOC (State of Charge) of hybrid and battery electric vehicles[66-70]. Some studies discussed Hinf battery fault estimation using observer-based methodology in HEV applications, while others explored algorithms for determining the temperature and thermal life of traction motors in commercial HEVs[71-72].

In 2010, Ip et al.[73] proposed a two-step model for city planning and designing refuelling infrastructure for BEVs. The first step segments road traffic and demands into clusters automatically, and the second step assigns stations to demand clusters using linear programming optimization. Cuma et al.[74] compared estimation strategies and methodologies used in hybrid and battery-electric vehicles in 2015. BEVs are equipped with an electric motor driven by a battery, effectively replacing the conventional Internal Combustion Engine Vehicle (ICEV) and fuel tank. When not in operation, BEVs are connected to a charging terminal for recharging[75-76].

Multiple studies have introduced estimation techniques for examining the SOC of lead-acid batteries, encompassing conventional methods like open circuit voltage and Ampere-hour counting[77-80]. Fuzzy logic-based algorithms and linear model tree methods are utilized for estimating the SOC of sealed lead-acid batteries[81]. Batteries of Li-ion types are commonly employed in hybrid EVs because of their substantial power capacity, long life cycle, and significant energy storage capabilities[82-83]. EVs can be categorized based on their charging time, driving range, and maximum load. Charging time depends on battery capacity and the type of battery used while driving range can vary from 20 km to 400 km per charge[84]. In developing nations, such as India, there is a growing interest in hybrid electric vehicles due to improvements in EVs, and innovations are expected to reduce production costs in the future. Table 2 presents a summary of the distinction between electric and hybrid vehicles.

| Table 2 Comparison of hybrid vehicles and electric vehicles |

1.3 Battery Thermal Management System

As the use of EVs increases, it becomes important to develop effective batteries. One of the major challenges for developing better BTMS (Batery Thermal Management System) is the thermal degradation of batteries, which affects the range of EVs. The primary goal of BTMS is to regulate the temperature of the battery cell and enhance its overall lifespan. Li-ion batteries are widely used for energy storage in EVs, but they encounter several challenges, such as reduced efficiency at extreme temperatures, shortened electrode life in high-temperature conditions, and potential implications on performance, cost, reliability, and safety due to thermal runaway. For the long-term success of EVs, an efficient thermal battery management system is crucial. Optimal operating conditions for lithium-ion batteries typically fall within the temperature range of 25 ℃ to 40 ℃, as the battery's life degrades when temperatures exceed 50 ℃.

1.4 Hybridization FactorVehicles can be categorized based on their hybridization factor, a measure that contributes to enhancing mileage, commonly expressed as Miles Per Gallon (MPG) or Miles Per Gallon Gasoline-equivalent (MPGe). MPGe is particularly applicable for plug-in hybrid electric vehicles, where 0.00337 MWh of electrical energy is considered equivalent to the energy content of a gallon of gasoline[85]. The hybridization factor for hybrid or electric vehicles represents the proportion of the overall generated power by the electric motor to the overall power generated[28], expressed as follows:

| $ \text { Hybridization Factor }=P_{\mathrm{EM}} /\left(P_{\mathrm{EM}}+P_{\mathrm{ICE}}\right) $ | (1) |

where PICE indicates the overall power output of the IC engine and PEM denotes the aggregate power output of the electric motor. The Hybridization Factor (HF) is 1 for all-electric vehicles and 0 for conventional cars.

1.5 Current Scenario of Electric VehicleAs of now, the EV market is quite small with only around 2000 units sold per year for the past few years in India[86]. However, there is a goal to achieve 100% electric vehicle sales by 2030, this implies that the compound yearly growth rate must be 28.12% starting from 2020[87]. The first electric car in India, the Reva by Mahindra, was launched in 2001 but sales were low. In 2010, Toyota launched the Prius hybrid model, followed by the introduction of the Camry hybrid in 2013. Some cities have also started pilot programs for electric buses and hybrid vehicles.

To promote the utilization of electric vehicles, various cities, and states in India have taken steps to encourage their adoption. As an illustration, the Municipal Transport Corporation of Bangalore has implemented electric transport services along a heavily trafficked corridor in the city. In Ludhiana city, similar survey was conducted, which unveiled that 36% of current car and two-wheeler owners expressed interest in transitioning to electric vehicles. The Telangana state government has made a notable announcement, stating that electric vehicle owners will be exempt from paying road tax. Additionally, the Electricity Regulatory Commission of Telangana State has approved a charging tariff of INR 6 for EVs and established a uniform service cost for the entire state at INR 6.04/kWh[88].

The government of Hyderabad is actively exploring the possibility of replacing diesel-run public transit vehicles with electric alternatives. Additionally, the Hyderabad metro rail has collaborated alongside the Power Grid Corporation (PGC) of India Ltd to provide EV charging facilities at metro stations.

In New Delhi, the government has secured approval for establishing more than 135 charging stations open to the public throughout the capital city. They have also introduced a draft policy to convert 25% of their vehicles to EVs by 2023. This endeavour involves offering various incentives to encourage the adoption of EVs and setting up adequate charging infrastructure. Furthermore, on the Pune-Mumbai highway, a private firm called Magenta Power is actively working on establishing EV charging infrastructure to support the growing electric vehicle market[89].

2 Government Schemes to Promote EVs 2.1 National Electric Mobility Mission Plan (NEMMP) 2020The Indian government launched the NEMMP 2020, aiming to:

a) Reduce environmental harm from fossil fuel vehicles.

b) Strengthen national energy security.

c) Boost domestic manufacturing in the EV sector.

Key objectives include deploying 5-7 million EVs by 2020, saving 2.2-2.5 million metric tons of fossil fuel, and reducing CO2 emissions by 1.3%-1.5%. The NEMMP highlights the need for government incentives and collaboration between industry and academia to meet these targets. Additionally, a goal of generating 0.1 MW of solar power by 2022 was set to improve the sustainability of EV charging.

2.2 FAME Ⅱ SchemeThe Faster Adoption and Manufacturing of Electric Vehicles (FAME Ⅱ) plan, launched in 2019[90], was allocated 10000 crore to encourage the adoption of EVs through:

a) Providing incentives for EV purchases.

b) Establishing charging infrastructure.

This policy, expected to last three years, aims to enhance the EV ecosystem and boost EV manufacturing.

2.3 Strategic Goals for 2030In 2017, NITI Aayog outlined a plan to reduce energy consumption in the automotive industry by adopting electric vehicles. Key goals include:

a) Achieving 100% pure EVs for intra-city public transport by 2030.

b) 40% of all new vehicle sales by 2030 to be electric, hybrid, or run on alternative fuels[91-92].

2.4 Challenges in the EV Market 2.4.1 Market barriersSeveral challenges hinder EV adoption in India:

a) Limited availability of trained technicians: A shortage of skilled technicians affects the repair and maintenance of EVs.

b) High cost of battery packs: EV batteries are expensive and need frequent replacements, making EVs costlier than traditional vehicles.

c) Limited EV options: The range of EV models is limited, affecting customer perception. Increased advertising and social media campaigns are needed to educate customers on the benefits of EVs.

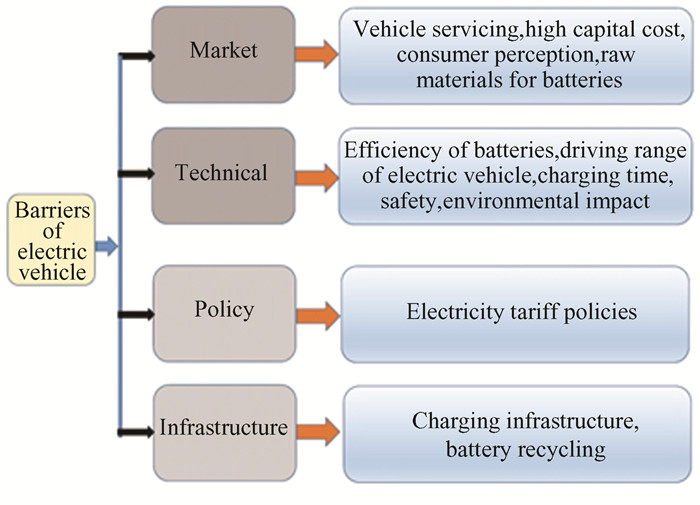

2.4.2 Supply chain constraintsThe production of EV batteries depends on scarce raw materials like lithium, nickel, and cobalt. As EV demand grows, the supply of these materials is expected to become increasingly strained, especially for lithium-ion batteries.Several obstacles impede the acceptance of the EV market in India, such as infrastructure barriers, and technical policy, are shown in Fig. 3.

|

Fig.3 Barriers to EVs |

2.5 Technical Barriers to EV Adoption 2.5.1 Battery efficiency and driving range

a) Battery lifespan: EV batteries typically last for 100000 miles or eight years, but degrade over time.

b) Driving range: BEVs offer a range under 250 km per charge, limiting their usability for long-distance travel. However, some newer models can reach up to 400 km[93].

c) PHEVs: Although PHEVs can drive on electric power alone, its range is often limited up to 50 km. After that, it will switch to the internal combustion engine, which reduce the benefit of emission free for longer trips. With the support of internal combustion engines, PHEVs offer ranges of over 500 km.

2.5.2 Charging timeThe time to charge an EV depends on:

a) Battery size: Larger batteries take longer to charge.

b) Charging rate: Faster chargers can significantly reduce charging time. Slow chargers (7 kW) can take up to 8 h, while rapid chargers can reduce this to 30 min for 145 km of range.

2.6 EV Charging TechnologiesEV chargers are categorized into three types:

a) Type 1 chargers: Standard 120 V outlets, used at homes, take about 8 h for a full charge.

b) Type 2 chargers: Used at public places or workplaces with 240 V outlets, taking about 4 h to charge for a range of 120-130 km.

c) DC fast charging: Converts AC to DC in the charging station, enabling rapid charging (30 min for 145 km), making it more convenient for EV users on the go.

However, charging rates decrease in colder temperatures, impacting the overall efficiency of the charging process.

2.7 Safety Standards of EVsTo comply with state and local regulations, electric vehicles must meet specific safety standards. This includes the batteries, which must undergo testing for conditions such as temperature, overcharge, short circuit, collision, fire, vibration, water immersion, and humidity. The design of these vehicles must also incorporate safety features such as insulation from high-voltage lines, and collision detection.

2.8 Environmental Impact of Electric VehiclesThe batteries used in electric vehicles, while contributing to their overall environmental friendliness, pose a challenge in terms of their sourcing. Elements used in these batteries are often extracted from mines or brine in the desert. This extraction process can have a significant impact on the environment, particularly concerning mining practices.

2.9 Government Policy for Electric VehiclesThe Indian government is taking steps to accelerate the acceptance of EVs. The plans encompass subsidizing the progress of EV charging facilities and providing clarity that operating EV charging stations does not necessitate a license. In addition to reducing the applicable rate of GST (Goods and Service Tax) over Li-ion batteries, the government is also providing incentives and concessions for EV buyers, and encouraging the public transport sector to shift towards electric vehicles.

2.10 Electric Vehicle InfrastructureTo meet the increasing need for electric vehicles, more charging infrastructure is needed to provide sufficient electrical energy. The existing absence of charging facilities in India is contributing to the low sales of electric vehicles. EV manufacturers must prioritize the design of chargeable batteries that facilitate the exchanging of discharged batteries with fully charged ones. Charging stations should strategically plan to charge batteries during off-peak times when electricity tariffs are lower, optimizing the charging process.

To accommodate diverse charging needs, setting up charging points at home should be an option, allowing EV owners to conveniently charge their vehicles overnight. For individuals lacking home charging facilities, the availability of charging points at workplaces or suitable stations, where they can stop for a few hours, becomes crucial. For quick charging on highways and in commercial complexes where vehicles stop briefly, fast charging stations should be readily accessible. However, it is crucial to consider that fast charging requires high current and voltage, which may increase the cost of EVs and impact battery life. Hence, an optimal solution could involve a well-balanced mix of both slow and fast chargers for EV owners.Electric vehicles use batteries that have a limited lifetime and will eventually wear out. Manufacturers, however, do not always clearly communicate the cost of battery replacement.

3 Optimization TechniquesThis paper delves into optimization techniques for EVs using various frameworks in different geographical locations. The explored frameworks encompass activity-based equilibrium scheduling, random utility model, stochastic model, driving pattern recognition, trip prediction model, probabilistic model, fuzzy-based model, data mining model, forecasting model, distributed optimization, hybrid PSO, ant colony optimization, household activity pattern, particle swarm optimization, linear programming, multi-objective, and adaptive model. The study aims to identify the potential benefits of charging characteristics for all EVs.

Moreover, it is important to note that if a battery replacement is needed outside the warranty period, it incurs additional expenses, as the old battery needs replacement with a new one. Additionally, the chemical elements present in these batteries, such as cobalt, lithium, nickel manganese, and titanium, not only impact the cost-effectiveness of the supply chain but also raise environmental concerns during the disposal of these batteries' elements. And optimization techniques for EVs in modern India, coupled with grid optimization, necessitate the development and application of advanced strategies tailored to the country's unique context. Here are several novel optimization approaches worthy of exploration.

3.1 Optimization Design and Models for EVs 3.1.1 Optimization design for EVs1) Multi-objective optimization: Developing multi-objective optimization models that account for conflicting goals, such as minimizing EV charging expenses, alleviating grid congestion, and maximizing renewable energy integration. These models aid decision-makers in identifying optimal solutions that strike a balance between economic, environmental, and societal factors.

2) Machine learning and data-driven optimization: Harnessing machine learning algorithms and data-driven methodologies to fine-tune EV charging schedules, forecast charging demands, and optimize grid operations in real time. Leveraging historical data, weather predictions, traffic trends, and EV user behaviour enhances the precision and efficiency of optimization models.

3) Distributed optimization and control: Exploring decentralized optimization and control algorithms facilitating coordinated decision-making among EVs, charging stations, and grid infrastructure. By decentralizing control mechanisms, the scalability, flexibility, and resilience of grid optimization solutions are enhanced while minimizing computational burden and communication load

4) Game theory and mechanism design: Applying game theory principles and mechanism design techniques to stimulate collaboration and coordination among stakeholders within the EV ecosystem. By devising incentive mechanisms aligning individual interests with collective goals, these strategies foster cooperation, optimize resource allocation, and mitigate potential conflicts.

5) Robust optimization and uncertainty quantification: Integrating robust optimization and uncertainty quantification methods to address uncertainties associated with EV demand fluctuations, renewable energy intermittency, grid disturbances, and market dynamics. Explicitly considering uncertainty in optimization models yields robust and adaptable solutions could be capable of performing optimally under diverse scenarios and conditions.

3.1.2 Optimization under constraintsFormulating optimization algorithms that explicitly account for constraints related to infrastructure limitations, regulatory mandates, and social equity considerations. By incorporating constraints into optimization models, these strategies ensure that solutions are both feasible and sustainable, aligning with societal needs while fulfilling desired objectives. The optimization techniques are developed for enhancing novelty in EVs focusing on a few factors, such as battery management systems(BMS), charging infrastructure optimization, range optimization, vehicle to grid integration, autonomous driving integration, shared mobility services.

1) BMS: Advanced algorithms for BMS optimize battery performance, longevity, and safety. Novel approaches include machine learning-based predictive analytics for state-of-health estimation, dynamic charging strategies to minimize degradation and adaptive thermal management for efficient temperature control.

2) Charging infrastructure optimization: Smart charging algorithms consider factors, such as grid load, energy pricing, and renewable energy availability to optimize EV charging schedules. Novel techniques leverage real-time data analytics, predictive modelling, and demand response strategies to reduce grid congestion, to maximize renewable energy utilization, and to minimize charging costs.

3) Range optimization: Innovations in range optimization focus on improving energy efficiency and extending driving range. This includes aerodynamic design enhancements, lightweight materials usage, regenerative braking optimization, and predictive energy management systems that adapt to driving conditions and user behaviour in real-time.

4) V2G integration: V2G optimization techniques enable bi-directional power flow between EVs and the grid, transforming vehicles into mobile energy storage units. Novel approaches involve decentralized energy trading platforms, blockchain technology for secure transactions, and optimization algorithms that balance grid demand and supply while maximizing revenue for EV owners.

5) Autonomous driving integration: Integration of EVs with autonomous driving technology presents opportunities for optimization in vehicle operation and energy management. Novel techniques include cooperative driving strategies for platooning, predictive route planning algorithms that consider energy consumption and traffic conditions, and vehicle-to-vehicle communication protocols for coordination and collision avoidance.

6) Shared mobility services: Optimization in shared mobility services involves dynamic fleet management, route optimization, and demand forecasting to maximize vehicle utilization and minimize wait times for users. Novel approaches leverage real-time data analytics, machine learning algorithms, and user behaviour modelling, to optimize service efficiency and profitability while reducing environmental impact.

These optimization techniques drive innovation and enhance the novelty of EVs by improving performance, efficiency, and user experience while contributing to the sustainability and decarbonisation of transportation systems. And also, researchers and practitioners can play a pivotal role in surmounting the challenges and barriers associated with electric vehicles in modern India, while concurrently optimizing the grid for sustainable and efficient operation. Various studies conducted by different authors worldwide, focusing on finding optimization techniques for EVs, are summarized in Table 3.

| Table 3 Optimization techniques with their impacts |

3.2 Challenges and Strategies for Optimal V2G Performance

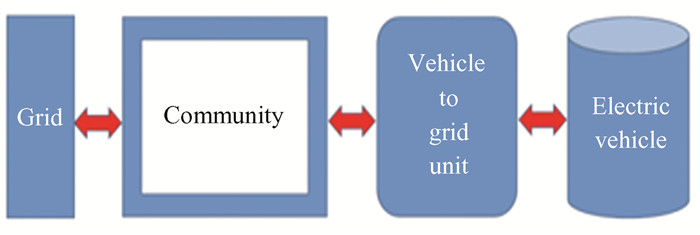

V2G technology was first proposed by Kempton et al. [108] as a way for parked electric vehicles to supply power to the grid using a bi-directional charger. This technology has been studied extensively to explore its impact on battery performance and degradation, as well as its potential benefits for managing energy storage in distribution systems [109-111]. Researchers have also compared the policies related to V2G and EVs in different countries and used empirical models to assess the viability of V2G, taking into account factors such as battery longevity and energy costs[112-115]. Even though there are many advantages to the V2G system, escalating the quality of plug-in electric vehicles may lead to the overloading of transformers, cables, and feeders, resulting in reduced effectiveness and potential voltage deviation and harmonics[116-117]. The V2G charging system is illustrated in Fig. 4.

|

Fig.4 V2G charging system |

Various optimization techniques have been proposed for V2G systems. Researchers worldwide have investigated the challenges and proposed different control strategies for optimal V2G performance. Table 4 provides an overview of the strategies published by different authors.

| Table 4 Vehicle-to-grid technology |

In a study by Tulpule et al.[118], the feasibility of V2G technology in parking lots across various locations in the USA was examined. The study compared the approach with home charging systems, evaluating factors like carbon dioxide emissions and cost. Additionally, another research effort focused on a parking lot in New Jersey, employing a straightforward approach to determine the potential of utilizing solar power to meet driving needs[119]. Moreover, some studies have explored the application of EV fleets at the city or regional level. For instance, in the Kansai area of Japan, smart charging methods were utilized to mitigate excess solar power[120]. These investigations contribute to valuable insights in the integration of EVs and renewable energy sources in different settings.

The large-scale deployment of V2G faces several socio-technical barriers. To assess the economics of V2G, Kempton et al.[121] introduced a lifetime battery energy function based on battery capacity, cycle lifetime, and DOD (Depth Of Discharge). V2G systems have been utilized in various countries to manage unpredictable energy demand or supply fluctuations.

For instance, Ekman[130] examined the collaboration between large EV fleets and high wind energy penetration in Denmark. These V2G systems can be integrated into hybrid, fuel cell, or pure battery electric vehicles, and their applicability has been studied across various energy markets, including peak load, base load, spinning reserve, and regulation services. To enable V2G, the vehicle requires a grid connection, communication with grid operations, and an on-board metering device[131]. An algorithm has been introduced to forecast Dynamic Line Rating (DLR), aimed at boosting the capacity of transmission lines. Additionally, it serves to prevent the curtailment of renewable energy sources, address power demands, and outages, and ensure equipment protection. Lawal et al.[132] added that their proposed algorithm's forecasting skill ranges from 91%-98%. It provides users with a range of capacities to select from each hour of the day in each month and a level of confidence that the chosen rating will not exceed the actual rating.

Drude et al.[133] investigated the capacity of grid-connected photovoltaic generation integrated into buildings in a sunny and warm climate for commercial buildings. In the past, vehicles were only capable of charging and not discharging, making grid support impossible[134-135]. However, numerous authors have conducted reviews on the technologies, benefits, costs, and challenges associated with V2G technology[136-139]. They have explored the optimal management of V2G systems and residential microgrids, as well as the feasibility of electric vehicle contribution to grid ancillary services.

Case studies[140-144] conducted in the USA compared plug-in type electric vehicles with hybrid electric vehicles and found that a mix of generating power plants reduced CO2 emissions by 25% in the short term and 50% in the long term. V2G vehicles with the capability can act as backup for sources of renewable power, such as wind and solar power, supporting the efficient integration of intermittent power production. Electric vehicles can also facilitate G2V and V2G interactions to maximize profits in the smart distribution system.

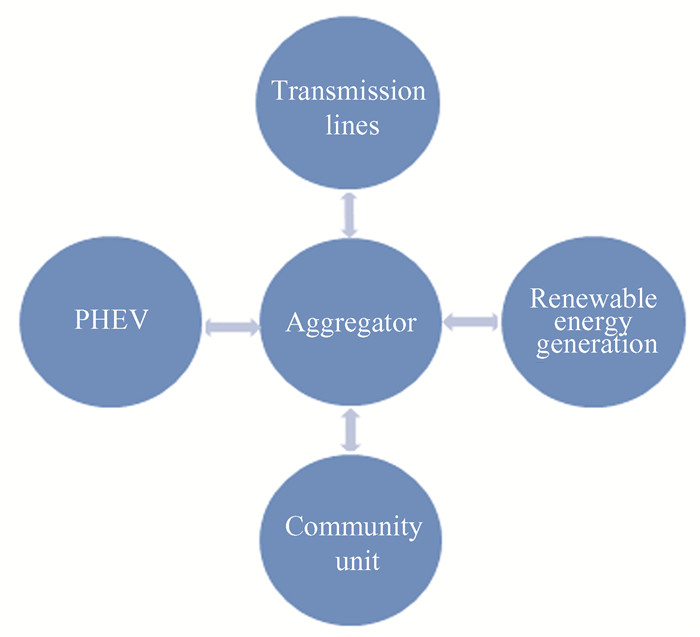

To minimize the impact of EV discharging and charging over the grid, the multiverse based multi-objective optimization algorithm has been employed. The aggregator of a V2G system collects individual plug-in EV data, detects and records the SOC (State of Charge) of individual vehicles, and interfaces with independent system operators[145-156].

To ensure efficient operation and reliability by dynamically adjusting the ratings of transmission lines based on real-time conditions, while also accounting for the potential loss of any single component in the system (N-1 reliability).

This integrated framework aims to enhance system performance, minimize operational risks, and maintain grid stability in the face of uncertainties and contingencies. It states EENS can be improved by 50% by using a DTR-NTO (Dynamic Thermal Rating-Network Topology Optimization) combination[157]. Fig. 5 illustrates the aggregator of a V2G system.

|

Fig.5 V2G System with aggregator |

4 Future Scope of Work

Looking forward, the realm of EVs and grid optimization in India offers promising avenues for future research and action. Firstly, ongoing empirical research is essential to collect data on EV adoption patterns, charging behaviours, and grid impacts across different regions of the country. Conducting longitudinal studies to monitor the growth of EV markets and infrastructure can yield valuable insights into emerging trends and challenges.

Secondly, there is room for exploring innovative business models, financing strategies, and public-private collaborations to expedite the deployment of EV charging infrastructure and overcome financial hurdles. Partnerships, involving utilities, mobility providers, real estate developers and technology firms, can unlock fresh investment opportunities and stimulate market expansion.

Furthermore, future research should prioritize the development of advanced grid optimization algorithms, demand-side management techniques and smart grid solutions, tailored specifically to India's unique context. These solutions must prioritize reliability, affordability, and sustainability while maximizing the integration of renewable energy sources and minimizing environmental footprints.

Moreover, interdisciplinary research is necessary to assess the socio-economic, environmental, and equity implications of EV adoption and grid optimization strategies. Analysing the distributional impacts of EV policies, accessing to charging infrastructure in underserved areas, and the potential for job creation, can inform more inclusive and equitable policy frameworks.

This paper also addresses the critical issues and leads to positive outcomes to the society:

1) Environmental benefits: EVs offer the potential to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and air pollution, improving public health and environmental quality.

2) Energy security: By promoting EV adoption and grid optimization for renewable energy integration, India can enhance energy security and reduce reliance on imported fossil fuels, mitigating vulnerability to global market fluctuations.

3) Economic opportunities: The transition to EVs and grid optimization presents economic opportunities, including job creation, innovation, and economic growth. It fosters a thriving electric mobility ecosystem, stimulating entrepreneurship and investment, and promoting economic development.

4) Climate change mitigation: Vehicles powered by renewable energy sources can help mitigate climate change by reducing greenhouse gas emissions from the transport sector. Promoting EV adoption and integrating renewable energy into the grid contribute to meeting climate change mitigation goals and safeguarding the planet for future generations.

5 ConclusionsThis paper provides a thorough examination of the literature, offering insights and recommendations for research on the market penetration rates of HEVs, PHEVs, and BEVs in the Indian market. Despite their higher initial costs compared to traditional vehicles, these alternatives offer significant long-term fuel economy and economic advantages to buyers, automakers, society, and policymakers. Recent efforts by the Indian government, along with various subsidies, are expected to drive the adoption of e-mobility in the country.

Moreover, the development of the V2G concept is identified as crucial in providing energy to the grid or charging the battery during times when non-conventional energy sources are unavailable. This facet is vital for bolstering energy security, encouraging the use of renewable energy, and addressing global warming concerns. The primary contribution of this paper lies in its comprehensive examination of the challenges and barriers faced by EVs in India, aiming to offer valuable insights and facilitate their successful integration into the market.

Through a detailed analysis of existing literature and a critical evaluation of factors like infrastructure limitations, policy frameworks, consumer perceptions, and grid constraints, several significant hurdles, hindering widespread EV adoption in India, are identified. A key conclusion drawn is the critical need for holistic strategies that address interconnected challenges facing EV adoption and grid optimization. These solutions must be tailored to India's unique socio-economic, infrastructural, and regulatory landscape, considering diverse stakeholder needs.

Collaboration among government agencies, industry players, research institutions, and civil society is emphasized as essential to drive progress and collectively overcome these challenges. Additionally, urgent policy interventions, investment incentives, and regulatory reforms are needed to expedite the deployment of EV charging infrastructure, bolster grid capacity and resilience, and build up consumer confidence in EV technology.

Initiatives, such as simplifying permitting processes, incentivizing private investment in charging infrastructure, and integrating renewable energy sources into the grid, are highlighted as pivotal steps to surmount barriers and foster a transition towards a sustainable electric mobility future in India.

This paper serves as a valuable resource for researchers interested in studying the market penetration rates of HEVs, PHEVs, and BEVs in the Indian market. It provides a comprehensive examination of the literature, offering insights and recommendations for further research in this area.

Researchers can benefit from the paper's analysis of the challenges and barriers faced by EVs in India, including factors such as infrastructure limitations, policy frameworks, consumer perceptions, and grid constraints. By understanding these hurdles, researchers can identify areas for further investigation and develop strategies to address them.

Moreover, the paper highlights the importance of holistic strategies that consider the interconnected challenges facing EV adoption and grid optimization. This insight can guide researchers in designing comprehensive studies that consider the socio-economic, infrastructural, and regulatory landscape of India.

Furthermore, the emphasis on collaboration among government agencies, industry players, research institutions, and civil society underscores the importance of interdisciplinary research and stakeholder engagement in driving progress. Researchers can use this as a basis for forming partnerships and collaborations to address the challenges identified in the paper.

Overall, the paper offers valuable insights and recommendations that can inform future research efforts aimed at facilitating the successful integration of electric vehicles into the Indian market and advancing the transition towards a sustainable and electric mobility future.

| [1] |

Doucette R T, McCulloch M D. Modelling the prospects of plug-in hybrid electric vehicles to reduce CO2 emissions. Applied Energy, 2011, 88(7): 2315-2323. DOI:10.1016/j.apenergy.2011.01.045 (  0) 0) |

| [2] |

Kailashkumar B, Elanchezhiyan M. Powering ahead: Current landscape of the electric vehicles (EV) in India. International Journal of Environment and Climate Change, 2024, 14(1): 639-647. DOI:10.9734/ijecc/2024/v14i13879 (  0) 0) |

| [3] |

Kempton W, Tomić J. Vehicle-to-grid power implementation: from stabilizing the grid to supporting large-scale renewable energy. Journal of Power Sources, 2005, 144(1): 280-294. DOI:10.1016/j.jpowsour.2004.12.022 (  0) 0) |

| [4] |

Bessa R J, Matos M A. Economic and technical management of an aggregation agent for electric vehicles: A literature survey. European Transactions on Electrical Power, 2012, 22(3): 334-350. DOI:10.1002/etep.565 (  0) 0) |

| [5] |

Daina N, Sivakumar A, Polak J W. Modelling electric vehicles use: A survey on the methods. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 2017, 68(part1): 447-460. DOI:10.1016/j.rser.2016.10.005 (  0) 0) |

| [6] |

Koyanagi F, Uriu Y. Modelling power consumption by electric vehicles and its impact on power demand. Electrical Engineering in Japan, 1997, 120(4): 40-47. DOI:10.1002/(SICI)1520-6416(199709)120:4%3C40::AID-EEJ6%3E3.0.CO;2-P (  0) 0) |

| [7] |

Kang J E, Recker W W. An activity-based assessment of the potential impacts of plug-in hybrid electric vehicles on energy and emissions using 1-day travel data. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment, 2009, 14(8): 541-556. DOI:10.1016/j.trd.2009.07.012 (  0) 0) |

| [8] |

Dong J, Liu C, Lin Z. Charging infrastructure planning for promoting battery electric vehicles: An activity-based approach using multiday travel data. Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies, 2017, 38: 44-55. DOI:10.1016/j.trc.2013.11.001 (  0) 0) |

| [9] |

Weiller C. plug-in hybrid electric vehicle impacts on hourly electricity demand in the United States. Energy Policy, 2011, 39(6): 3766-3778. DOI:10.1016/j.enpol.2011.04.005 (  0) 0) |

| [10] |

Sundström O, Binding C. Charging service elements for an electric vehicle charging service provider. Proceedings of the Power and Energy Society General Meeting. Piscataway: IEEE, 2011: 1-6. DOI: 10.1109/PES.2011.6038982.

(  0) 0) |

| [11] |

Galus M D, Vayá M G, Krause T, et al. The role of electric vehicles in smart grids. Wiley Interdisciplinary Review: Energy and Environment, 2013, 2(4): 384-400. DOI:10.1002/wene.56 (  0) 0) |

| [12] |

Brady J, O'Mahony M. Modelling charging profiles of electric vehicles based on real-world electric vehicle charging data. Sustainable Cities and Society, 2016, 26: 203-216. DOI:10.1016/j.scs.2016.06.014 (  0) 0) |

| [13] |

Morrissey P, Weldon P, Mahony M O. Future standard and fast charging infrastructure planning: An analysis of electric vehicle charging behaviour. Energy Policy, 2016, 89: 257-270. DOI:10.1016/j.enpol.2015.12.001 (  0) 0) |

| [14] |

Foley A, Tyther B, Calnan P, et al. Impacts of electric vehicle charging under electricity market operations. Applied Energy, 2013, 101: 93-102. DOI:10.1016/j.apenergy.2012.06.052 (  0) 0) |

| [15] |

Steinhilber S, Wells P, Thankappan S. Socio-technical inertia: Understanding the barriers to electric vehicles. Energy Policy, 2013, 60: 531-539. DOI:10.1016/j.enpol.2013.04.076 (  0) 0) |

| [16] |

Yu H, Tseng F, McGee R. Driving pattern identification for EV range estimation. Proceedings of the IEEE International Electric Vehicle Conference (IEVC). Piscataway: IEEE, 2012: 1-7. DOI: 10.1109/IEVC.2012.6183207.

(  0) 0) |

| [17] |

Hayes J G, de Oliveira R P R, Sean V, et al. Simplified electric vehicle power train models and range estimation. Proceedings of the IEEE Vehicle Power and Propulsion Conference (VPPC). Piscataway: IEEE, 2011: 1-5. DOI: 10.1109/VPPC.2011.6043163.

(  0) 0) |

| [18] |

Salah F, Ilg J P, Flath C M, et al. Impact of electric vehicles on distribution substations: A Swiss case study. Applied Energy, 2015, 137: 88-96. DOI:10.1016/j.apenergy.2014.09.091 (  0) 0) |

| [19] |

Hartmann N, Özdemir E D. Impact of different utilization scenarios of electric vehicles on the German grid in 2030. Journal of Power Sources, 2011, 196(4): 2311-2318. DOI:10.1016/j.jpowsour.2010.09.117 (  0) 0) |

| [20] |

Yang F, Sun Y, Shen T. Nonlinear torque estimation for vehicular electrical machines and its application in engine speed control. Proceedings of the 2007 IEEE International Conference on Control Applications. Piscataway: IEEE, 2007: 1382-1387. DOI: .1109/CCA.2007.4389429.

(  0) 0) |

| [21] |

Yu X, Shen T, Li G, et al. Regenerative braking torque estimation and control approaches for a hybrid electric truck. Proceedings of the 2010 American Control Conference. Piscataway: IEEE, 2010: 5832-5837. DOI: 10.1109/ACC.2010.5530501.

(  0) 0) |

| [22] |

Yu X, Shen T, Li G, et al. Model-based drive shaft torque estimation and control of a hybrid electric vehicle in energy regeneration mode. Proceedings of the 2009 ICCAS-SICE. Piscataway: IEEE, 2009: 3543-3548.

(  0) 0) |

| [23] |

Yin D, Hori Y. A novel traction control of EV based on maximum effective torque estimation. Proceedings of the 2008 IEEE Vehicle Power and Propulsion Conference. Piscataway: IEEE, 2008: 1-6. DOI: 10.1109/VPPC.2008.4677424.

(  0) 0) |

| [24] |

Yin D, Hori Y. A new approach to traction control of EV based on maximum effective torque estimation. Proceedings of the 2008 34th Annual Conference of IEEE Industrial Electronics. Piscataway: IEEE, 2008: 2764-2769. DOI: 10.1109/IECON.2008.4758396.

(  0) 0) |

| [25] |

Yin D, Oh S, Hori Y. A novel traction control for EV based on maximum transmissible torque estimation. Proceedings of the IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics. Piscataway: IEEE, 2009: 2086-2094. DOI: 10.1109/TIE.2009.2016507.

(  0) 0) |

| [26] |

Lu L, Han X, Li J, et al. A review on the key issues for lithium-ion battery management in electric vehicles. Journal of Power Sources, 2013, 226: 272-288. DOI:10.1016/j.jpowsour.2012.10.060 (  0) 0) |

| [27] |

Panday A, Bansal H O. A review of optimal energy management strategies for hybrid electric vehicle. International Journal of Vehicular Technology, 2014(2014): 1-19. DOI:10.1155/2014/160510 (  0) 0) |

| [28] |

Tie S F, Tan C W. A review of energy sources and energy management system in electric vehicles. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 2013, 20: 82-102. DOI:10.1016/j.rser.2012.11.077 (  0) 0) |

| [29] |

Yong J Y, Ramachandaramurthy V K, Tan K M, et al. A review on the state-of-the-art technologies of electric vehicle, its impacts and prospects. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 2015, 49: 365-385. DOI:10.1016/j.rser.2015.04.130 (  0) 0) |

| [30] |

Richardson D B. Electric vehicles and the electric grid: A review of modelling approaches, impacts, and renewable energy integration. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 2013, 19: 247-254. DOI:10.1016/j.rser.2012.11.042 (  0) 0) |

| [31] |

Yang L, Teh J. Review on vulnerability analysis of power distribution network. Electric Power Systems Research, 2023, 224: 109741. DOI:10.1016/j.epsr.2023.109741 (  0) 0) |

| [32] |

Lai C M, Teh J. Network topology optimization based on dynamic thermal rating and battery storage systems for improved wind energy penetration and reliability. Journal of Applied Energy, 2022, 305: 117837. DOI:10.1016/j.apenergy.2021.117837 (  0) 0) |

| [33] |

Alanazi F. Electric vehicles: Benefits, challenges, and potential solutions for widespread adaptation. Applied Sciences, 2023, 13(10): 6016. DOI:10.3390/app13106016 (  0) 0) |

| [34] |

Wikipedia. Plug-in electric vehicles in India. [2025-01-19]. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Plug-in_electric_vehicles_in_India.

(  0) 0) |

| [35] |

Climatelinks. Greenhouse gas emissions factsheet: India. https://www.climatelinks.org/resources/greenhouse-gas-emissions-factsheet-india.

(  0) 0) |

| [36] |

Su Y, Teh J, Chen C. Optimal dispatching for AC/DC hybrid distribution systems with electric vehicles: Application of cloud-edge device cooperation. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transport Systems, 2023, 25(3): 3128-3139. DOI:10.1109/TITS.2023.3314571 (  0) 0) |

| [37] |

Fuel cell electric tractor-trailers: technology overview and fuel economy. International Council on Clean Transportation (ICCT). [2022-07-18]. http://www.indiaenvironmentportal.org.in/content/473245/fuel-cell-electric-tractor-trailers-technology-overview-and-fuel-economy/.

(  0) 0) |

| [38] |

Su Y, Teh J. Two-stage optimal dispatching of AC/DC hybrid active distribution systems considering network flexibility. Journal of Modern Power Systems and Clean Energy, 2022, 11(1): 52-65. DOI:10.35833/MPCE.2022.000424 (  0) 0) |

| [39] |

Teh J, Lai C M, Cheng Y H. Impact of the real-time thermal loading on the bulk electric system reliability. IEEE Transactions on Reliability, 2017, 66(4): 1110-1119. DOI:10.1109/TR.2017.2740158 (  0) 0) |

| [40] |

Union of Concerned Scientists. Transportation technologies and innovation. https://www.ucsusa.org/transportation/technologies.

(  0) 0) |

| [41] |

NPTEL. NOC: Electric vehicles and renewable energy(Video). [2021-06-21]. https://archive.nptel.ac.in/courses/108/106/108106182/.

(  0) 0) |

| [42] |

Wikimili. Electric car use by country. [2025-02-17]. https://wikimili.com/en/Electric_car_use_by_country.

(  0) 0) |

| [43] |

Wu X, Hu X, Yin X, et al. Stochastic optimal energy management of smart home with PEV energy storage. IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid, 2016, 9(3): 2065-2075. DOI:10.1109/TSG.2016.2606442 (  0) 0) |

| [44] |

Bashash S, Moura S J, Forman J C, et al. plug-in hybrid electric vehicle charge pattern optimization for energy cost and battery longevity. Journal of Power Sources, 2011, 196(1): 541-549. DOI:10.1016/j.jpowsour.2010.07.001 (  0) 0) |

| [45] |

Hadley S W, Tsvetkova A A. Potential impacts of plug-in hybrid electric vehicles on regional power generation. The Electricity Journal, 2009, 22(10): 56-68. DOI:10.1016/j.tej.2009.10.011 (  0) 0) |

| [46] |

Kelly J C, MacDonald J S, Keoleian G A. Time-dependent plug-in hybrid electric vehicle charging based on national driving patterns and demographics. Applied Energy, 2012, 94: 395-405. DOI:10.1016/j.apenergy.2012.02.001 (  0) 0) |

| [47] |

Bradley T H, Frank A A. Design, demonstrations and sustainability impact assessments for plug-in hybrid electric vehicles. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 2009, 13(1): 115-128. DOI:10.1016/j.rser.2007.05.003 (  0) 0) |

| [48] |

Darabi Z, Ferdows M. Aggregated impact of plug-in hybrid electric vehicles on electricity demand profile. IEEE Transactions on Sustainable Energy, 2011, 2(4): 501-508. DOI:10.1109/TSTE.2011.2158123 (  0) 0) |

| [49] |

Hajimiragha A, Canizares C A, Fowler M W, et al. Optimal transition to plug-in hybrid electric vehicles in Ontario, Canada, considering the electricity-grid limitations. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics, 2010, 57(2): 690-701. DOI:10.1109/TIE.2009.2025711 (  0) 0) |

| [50] |

Peterson S B, Whitacre J F, Apt J. The economics of using plug-in hybrid electric vehicle battery packs for grid storage. Journal of Power Sources, 2010, 195(8): 2377-2384. DOI:10.1016/j.jpowsour.2009.09.070 (  0) 0) |

| [51] |

Qiang J, Ao G, He J, et al. An adaptive algorithm of NiMH battery state of charge estimation for hybrid electric vehicle. Proceedings of the 2008 IEEE International Symposium on Industrial Electronics. Piscataway: IEEE, 2008: 1556-1561. DOI: 10.1109/ISIE.2008.4677229.

(  0) 0) |

| [52] |

García-Villalobos J, Zamora I, Knezović K, et al. Multi-objective optimization control of plug-in electric vehicles in low voltage distribution networks. Applied Energy, 2016, 180: 155-168. DOI:10.1016/j.apenergy.2016.07.110 (  0) 0) |

| [53] |

Weis A, Jaramillo P, Michalek J. Estimating the potential of controlled plug-in hybrid electric vehicle charging to reduce operational and capacity expansion costs for electric power systems with high wind penetration. Applied Energy, 2014, 115: 190-204. DOI:10.1016/j.apenergy.2013.10.017 (  0) 0) |

| [54] |

Zoepf S, MacKenzie D, Keith D, et al. Charging choices and fuel displacement in a large-scale demonstration of plug-in hybrid electric vehicles. Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board, 2013, 2385(1): 1-10. DOI:10.3141/2385-01 (  0) 0) |

| [55] |

Goel S, Sharma R, Akshay Kumar Rathore A K. A review on barrier and challenges of electric vehicle in India and vehicle to grid optimization. Transportation Engineering, 2021, 44: 100057. DOI:10.1016/j.treng.2021.100057 (  0) 0) |

| [56] |

Marano V, Onori S, Guezennec Y, et al. lithium-ion batteries life estimation for plug-in hybrid electric vehicles. Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE Vehicle Power and Propulsion Conference. Piscataway: IEEE, 2009: 536-543. DOI: 10.1109/VPPC.2009.5289803.

(  0) 0) |

| [57] |

Campbell I D, Gopalakrishnan K, Marinescu M, et al. Optimising lithium-ion cell design for plug-in hybrid and battery electric vehicles. Journal of Energy Storage, 2019, 22: 228-238. DOI:10.1016/j.est.2019.01.006 (  0) 0) |

| [58] |

Kramer S C B, Kroposki B. A review of plug-in vehicles and Vehicle-to-Grid capability. 2008 34th Annual Conference of IEEE Industrial Electronics. Piscataway: IEEE, 2008: 2278-2283. DOI: 10.1109/IECON.2008.4758312.

(  0) 0) |

| [59] |

Wirasingha S G, Schofield N, Emadi A. plug-in hybrid electric vehicle developments in the US: trends, barriers, and economic feasibility. Proceedings of the 2008 IEEE Vehicle Power and Propulsion Conference. Piscataway: IEEE, 2008: 1-8. DOI: 10.1109/VPPC.2008.4677702.

(  0) 0) |

| [60] |

Fernandez L P, San Román T G, Cossent R, et al. Assessment of the impact of plug-in electric vehicles on distribution networks. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems, 2010, 26(1): 206-213. DOI:10.1109/TPWRS.2010.2049133 (  0) 0) |

| [61] |

Ipakchi A, Albuyeh F. Grid of the future. IEEE Power and Energy Magazine, 2009, 7(2): 52-62. DOI:10.1109/MPE.2008.931384 (  0) 0) |

| [62] |

Fairley P. Speed bumps ahead for electric-vehicle charging. IEEE Spectrum, 2010, 47(1): 13-14. DOI:10.1109/MSPEC.2010.5372476 (  0) 0) |

| [63] |

Clement-Nyns K, Haesen E, Driesen J. The impact of charging plug-in hybrid electric vehicles on a residential distribution grid. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems, 2009, 25(1): 371-380. DOI:10.1109/TPWRS.2009.2036481 (  0) 0) |

| [64] |